Consider Titane a reverse-slasher: not merely because in place of the usual murderous man-child in gender distress, fueled by psychosexual rage to terrorize mainly (or most enthusiastically) his female victims, we have a gender-bending woman serial killer, primarily attracted to automobiles, and as heartlessly prone to disposing of men as well as women. (Her weapon, too, is bisexual—a metal knitting needle adopted as a hairpin—outwardly phallic, functionally feminine.) But structurally the genre is also flipped. We begin with violence and end on domesticity, the family home: the very site the villain endangers, or—depending on your perspective—that endangers the villain, for this is the birthplace of their depravity and their queerness imperils its “natural” order. This may well be the key to Julia Ducournau’s follow-up to Raw: a violent, determinedly graphic, sometimes illegible portrait of a wandering woman, trapped in her scarred skin, blindly grasping for something she cannot name because she has never known it. Perhaps, put that way, it sounds much less interesting, but underneath all the outlandish trappings—car-fucking, serial murdering, machine pregnancy—there is a simpler, almost poignant tale of what curious, unwieldly parts might make up a home.

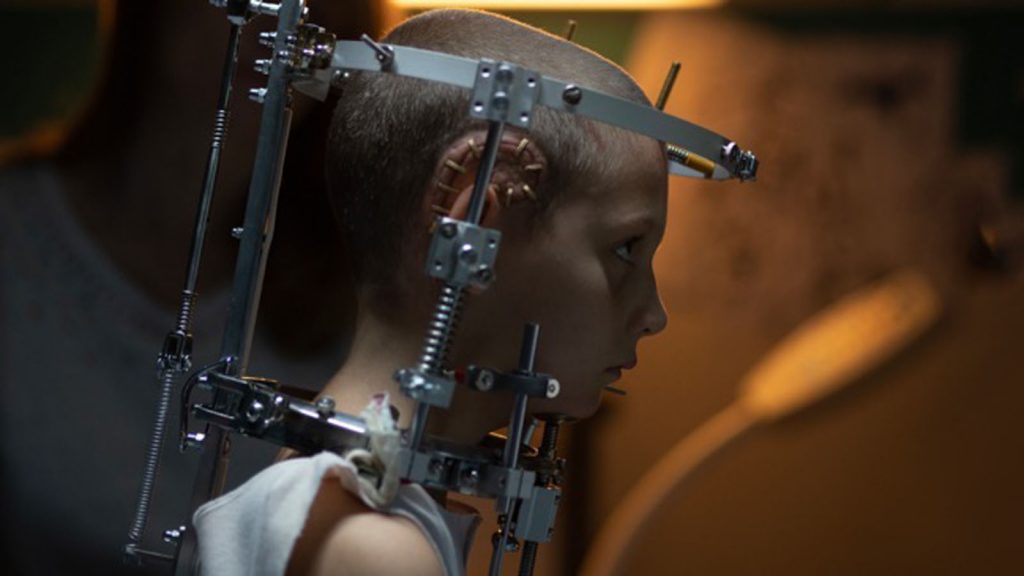

Naturally, what has been most feverishly discussed about Titane is the car-fucking. Admittedly it’s among the most unique sex scenes to ever grace the screen, but precisely how this consummation works—that is, what goes where and how the act manages to yield a pregnancy—is left a mystery. Slipping between close-ups and long shots, the film captures Alexia (Agathe Rousselle), our mechanophiliac, clinging to the seat belts as she and the car bounce up and down. The next morning she finds her panties soiled with motor oil. As a child she had been in a terrible car accident that required a titanium plate sewn into her skull. This may or may not be the source of her dysfunction, for she already shows traces of misanthropy and a fixation on vehicles in the film’s early moments. Eyes vacant, she hums to mimic the sound of the car’s engine, petulantly distracting her aloof father (an almost wordless but eerily effective Bertrand Bonello, a pillar of the New French Extremity to which Ducournau also belongs). Fathers turn out to be a rather crucial force here. In any case, he takes his eyes off the road to scold her, which causes their crash. But upon leaving the hospital, a crane-shaped scar forever engraved above her ear, she embraces the car.

This is how we come to find Alexia, now an adult, dancing professionally at an auto show. Given her particular affinity for the work, she has amassed a fan base of salivating men, one of whom stalks her into the parking lot after a show. When he assaults her, she slips the metal pin out of her hair and fatally stabs him in the ear. This, apparently, is her modus operandi, and sexual overtures, encouraged or not, only provoke her. Another human dalliance ends in a pile of dead bodies, and Alexia becomes a wanted woman. At the same time, her own body has begun to betray her; her belly grows at such an accelerated rate that the skin begins to itch and tear, seeping inky fluids. When she stumbles upon the digitally aged portrait of a boy named Adrien Legrand, who went missing a decade earlier, she decides to impersonate him. She shaves her head, breaks her nose, and straps down her breasts and burgeoning belly under baggy clothes, but later one suspects that it would have taken much less to convince the boy’s long-grieving father, Vincent (Vincent Lindon), who refuses a DNA test and readily brings Alexia home with him.

At this point, even the most charitable viewer may begin to feel duped; Titane reveals itself as being composed of two seemingly disparate parts. Aside from a cardinal commitment to abjection (the objectified-turned-monstrous femininity with all its flesh-ripping, orifice-leaking, and so on), the serial-killing half has little to do with the family-melodrama half. But there are hints that we were always watching the latter. After all, the film begins with one father’s remoteness and resolves with another’s dogged intimacy. Life as Alexia concludes when she shares one last silent, lingering look with her withholding birth dad—their communication exclusively a series of these fraught, mute glances, an unspoken chasm between them—right before she locks her parents inside their bedroom and sets the house ablaze. In hindsight, all signs point to Vincent: the aging, steroid-addicted captain of a firehouse, from the flame-decked Cadillac that Alexia grinds against to this past-scorching fire. Reborn as Adrien, she finds Vincent—appealingly charged with the ultramasculine legacy Lindon has forged for himself in French cinema—so mired in grief, so desperate for connection, that he emerges as an unexpectedly nurturing figure, custom-fitted for Alexia/Adrien’s peculiar maladjustment.

Unlike her own father, he pleads, then demands Alexia/Adrien speak to him; when that fails, Vincent insists his son dance with him, holding Alexia perilously close. In the past, intimacy had been a trigger, and predictably Alexia pulls out her killing needle, but Vincent bests her, physically and somehow emotionally. As much trapped in her new role as she is intrigued by all its new possibilities, Alexia slips into a strange domesticity with Vincent where filial boundaries are continually blurred. In one scene, she awkwardly injects him in the hip with steroids, and in another dancing scene—doubling the former, their bond fully cemented now—he loops his arm between her legs and lifts her onto his shoulders. Titane is at its richest here, where Ducourneau, an instinctively kinetic filmmaker, can build a fascinating tableau that pivots on its ambivalence. Sexual or not, ultimately we have a partnership of stunted souls, starved of affection—literalized through their brutally punished, bruised, helplessly transforming bodies—and who can each perform for the other the primal roles out of which they never grew: father and child.

Elsewhere, Ducourneau’s tendency to leave the implications behind her compositions unexplored does not work as well. Gender is a central preoccupation, albeit regrettably uninspired in its observations (of which there are few anyway). There is, of course, the car’s obvious links to sex and the presumed kinship between manhood and automobiles, which conceals the truer twinship between women and cars as objects of male fantasy and, more importantly, homosocial camaraderie. Curiously enough, the car is immobile here, rendered entirely symbolic. It no longer represents emancipation, and the home is no longer purely the province of trapped women. It is through Vincent and the hermetic, male domains into which he leads Alexia/Adrien that she first discovers the range of human communion. For better and worse, family dynamics are replicated at the firehouse, specifically in a sibling rivalry between Alexia and another firefighter, now displaced from Vincent’s attention. But if Alexia is never quite freed from her fetishized body—she still finds herself a gendered spectacle at the film’s end—these closing moments reveal where the film has located its truest interests: the not-merely-physical space in which families are made. 🩸

has a PhD in horror cinema and her work has been published in Film Comment, Reverse Shot, and MUBI Notebook, among others.

Though she’s not generally counted among the canon of horror’s distinguished performers, perhaps none can boast a more sprawling and diverse corpus than Carla Gugino.

BY KELLI WESTON | May 9, 2024

The opening image of David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future is arresting, enigmatic, exquisite, revealing an enormous capsized ship...

BY JOSÉ TEODORO | June 7, 2022

Audiences and filmmakers alike can’t seem to get enough of body horror. The Soskas went for it full-throttle with their 2019 remake of Cronenberg’s Rabid (an early work by one of the subgenre’s originators).

BY LAURA KERN | April 19, 2022

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021