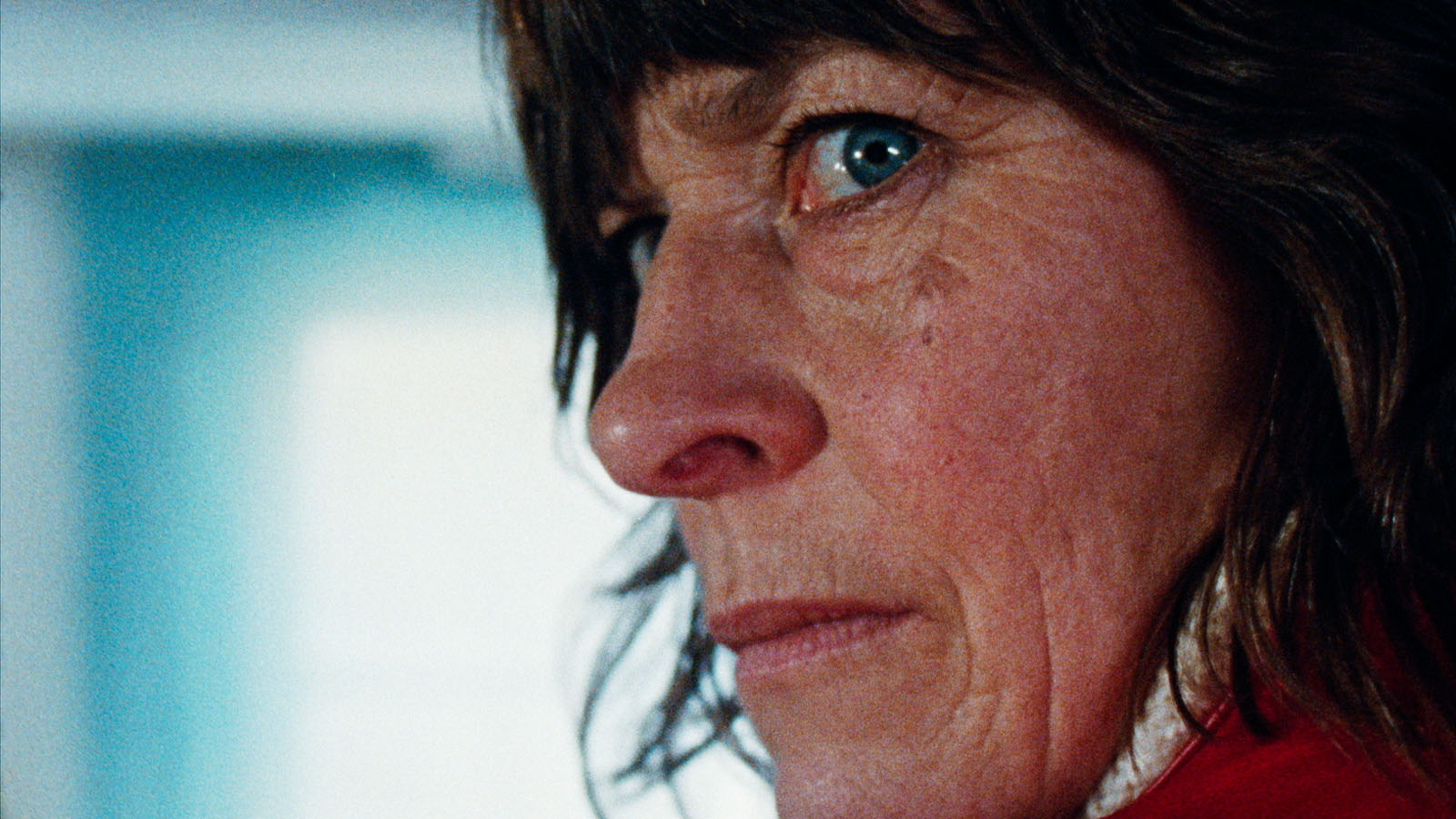

It is springtime 1973, and the days are bright on a small island off the coast of Cornwall. A horticulturist (Mary Woodvine), known only as the volunteer, is the island’s sole inhabitant. Or is she? We observe her daily activities: she walks the wind-sculpted cliffs, takes temperature readings, examines a tiny patch of rare orchids, listens to a stone she drops down a long-retired mineshaft, starts up a small gas generator, makes tea, plays the radio, writes in a ledger—every day reads “No change”—and eventually tucks herself into bed with a book titled A Blueprint for Survival, whose cover boasts that after reading it, “nothing seems quite the same.” The thrum of repetition and routine lays a hypnotic foundation for the accrual of strangeness that overtakes Eyns Men, English writer-director Mark Jenkin’s second feature, which is at once spartan and hallucinatory, a ghost story whose progress takes us from spare realism to phantasmagoria. In a key scene, a visiting fisherman asks the volunteer whether she likes being there, on her own. The volunteer replies, “I’m not on my own.”

Solitude and desolation have a way of summoning ghosts. The sense of the past impinging on the volunteer’s present takes myriad forms, some subtle, such as the fuzzy, ominous messages emanating from the radio or a shard from the wreckage of an old lifeboat, and others are ostentatious, like the sudden appearance of miners, bal maidens, a pretty young girl (Flo Crowe), or sprigs of lichen bursting forth from the aforementioned orchids—and from the wound on the volunteer’s stomach. (This last development, locating the uncanny within the body rather than the mind, made me think of the appearance of radish sprouts on the protagonist’s legs in Kobo Abe’s novel Kangaroo Notebook.) Some of these manifestations, such as that of the miners, suggest their own origin stories, while others, namely that of the young girl, retain their enigmatic status until the film’s end. Enys Men features little in the way of dialogue, and Jenkin’s focus is clearly on stacking revelations and creating a highly specific atmosphere rather than developing plot or offering backstory. He and his handful of collaborators have created a world where weird things happen, time collapses, and land holds memory. “Enys Men” means “stone island” in Cornish, and, indeed, these old stones, isolated by cold salt water for millennia, seem inscribed with historical traumas.

The decision to set Enys Men 50 years in the past—the dates are clearly visible in the ledger—seems deliberate and precise. Besides its utility as a period whose technology serves the needs of the story, the choice of 1973 is echoed in the film’s visual elements, such as its ostentatious zooms and bold color palette: Jenkin, who served as cinematographer, shot the film on 16mm and savors that format’s tendency toward saturation, rendering the sea a steely blue and the volunteer’s red rain slicker the hue of fresh blood. (The latter itself seems emblematic of 1973, the year of Don’t Look Now and the most famous red rain slicker in cinema history.) Jenkin also served as his own composer, and his ambient score, in tandem with the environmental sounds and the rattling roar of the generator, infuses the film with a general feeling of unseen presence. Like Robert Eggers, Guy Maddin, or Peter Strickland, Jenkin seems drawn toward the tools, techniques, and aesthetics of cinema’s past. Whether his films will reach the imaginative heights of those other filmmakers’ best works remains to be seen, but with Enys Men, he has crafted something both familiar and distinctive, beautiful and eerie, enveloping us in a quiet creepiness that lingers in the senses long after it’s over.

is a freelance critic and playwright.

Drawing inspiration from the special bleary-eyed ambiance of vintage witching-hour television, this found-footage curio from Australia’s...

BY JOSÉ TEODORO | March 22, 2024

We go to the movies to see ghosts, whether they be the likenesses of long-gone actors, objects, or edifices, or the suggestion of specters imprinted in the gloom of otherwise benign images.

BY JOSÉ TEODORO | February 2, 2023

From its opening image of ocean waves stuttering slowly behind a sheet of steely rain to its final vista of human detritus turned into cosmic junk...

BY JOSÉ TEODORO | September 12, 2022

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021