High-concept, no-frills horror is writer-director-editor-composer Andy Mitton’s modus operandi. While his four features (the first two co-directed with Jesse Holland) address vaster subjects of death and the afterlife, there’s also a recognition that dread lurks in the most mundane places. Terror is inescapable. It’s found in your dream house or your actual dreams, or has literally latched itself onto you. Mitton’s is some of the sharpest writing in modern horror. Even when relying on familiar elements, his films feel like something altogether their own. And in an age when most movies’ runtimes are needlessly bloated, he is also a master of concision, with only one of his films (just barely) exceeding 90 minutes—a brevity that in no way shortchanges his characters. Their relationships, especially of the familial variety, are given more-than-adequate breathing space; there’s just no fat to trim.

This unusual deep-thinking but stripped-bare approach turns out to be a natural fit for the quarantine film. “COVID movies” immediately faced resistance from those not interested in reexperiencing the harsher beginnings of something we have yet to escape, but with The Harbinger, Mitton makes the strongest case yet for this subgenre’s existence. It’s the first film to truly capture the emotional horror of those early days of lockdown, when we wiped down groceries and toilet seats and were petrified of getting within six feet of others, catching the virus, or, worse, infecting a loved one. Venturing anywhere public felt almost like a personal attack on your chosen hive members, and The Harbinger’s heroine Monique (Gabby Beans) is certainly treated like a betrayer by her father and brother (Raymond Anthony Thomas and Myles Walker) after announcing that she might need to burst their quarantine bubble. They are in the midst of celebrating the dad’s birthday when Monique receives a phone call for help from an old college buddy, Mavis (Emily Davis)—whom we see traumatized in the film’s opening sequence, clawing her arm to a bloody mess while mysteriously imploring herself to “wake up”—and because her friend has no one else, Monique decides to trade her upstate security for the hell of an unknown Queens apartment building. En route, the fear of traveling is palpable, and before even making it to Mavis’s front door, she encounters a very sick child and an unhinged neighbor who refuses to wear a mask and keep her distance in shared spaces. But once behind closed doors, the two hesitantly decide to go maskless and things temporarily feel “normal” again—just friends catching up over drinks, joyful for the companionship.

But this place is no safe haven: Mavis reveals she’s been having terrible, persistent nightmares, to the extent that she often doesn’t know when she’s in or out of them, and is losing hours, even days, of her life. And when she does wake, it’s just to be thrown back into the real nightmare of the pandemic. Monique herself begins having horrific dreams, but still questions her friend’s mental state. Willing to play along, she offers to sketch Mavis’s description of what she has been seeing in her sleep, and recognizes it as the plague doctor, a historical figure unfamiliar to Mavis. Posting the image online in hopes of locating others in the same predicament leads to a chaotic call with a demonologist (Laura Heisler), who’s forced to do consultations via Zoom as her young children run around in the background. She introduces the idea of a harbinger—an evil spirit that thrives on the isolation of the pandemic, because it provides more space for exploiting fear, ultimately taking over its victim completely. This not-exactly-hopeful theory sets the stage for the increasingly surreal series of mostly dream-life sequences that the film becomes.

Pre-pandemic, Mitton’s first solo directorial outing, The Witch in the Window (2018), already introduced a politically and environmentally unpredictable world, as well as a parent’s accompanying anxieties about raising kids under these oppressive conditions. In a time when it’s not just porn that accounts for unsavory internet viewing, 12-year-old Finn (Charlie Tacker) is caught by his mom (Arija Bareikis) watching a graphic real-life beheading video, and is shipped off to stay with his father (Alex Draper), the new owner of a big old house in Vermont. He claims he intends to flip it, a past hobby of his, but we soon learn he has longer-term plans. Like the apartment in The Harbinger, the house here takes on a villain-like role. The hopes that the place could represent a positive shift in the plight of a family divided, with reconnection just out of reach, are smashed by a genuinely spine-chilling old witch (Carol Stanzione) who lives there and has no interest in giving up ownership of her home. She, like the plague doctor, gets inside people’s heads, making it progressively harder to know what’s real and what’s orchestrated by mind games.

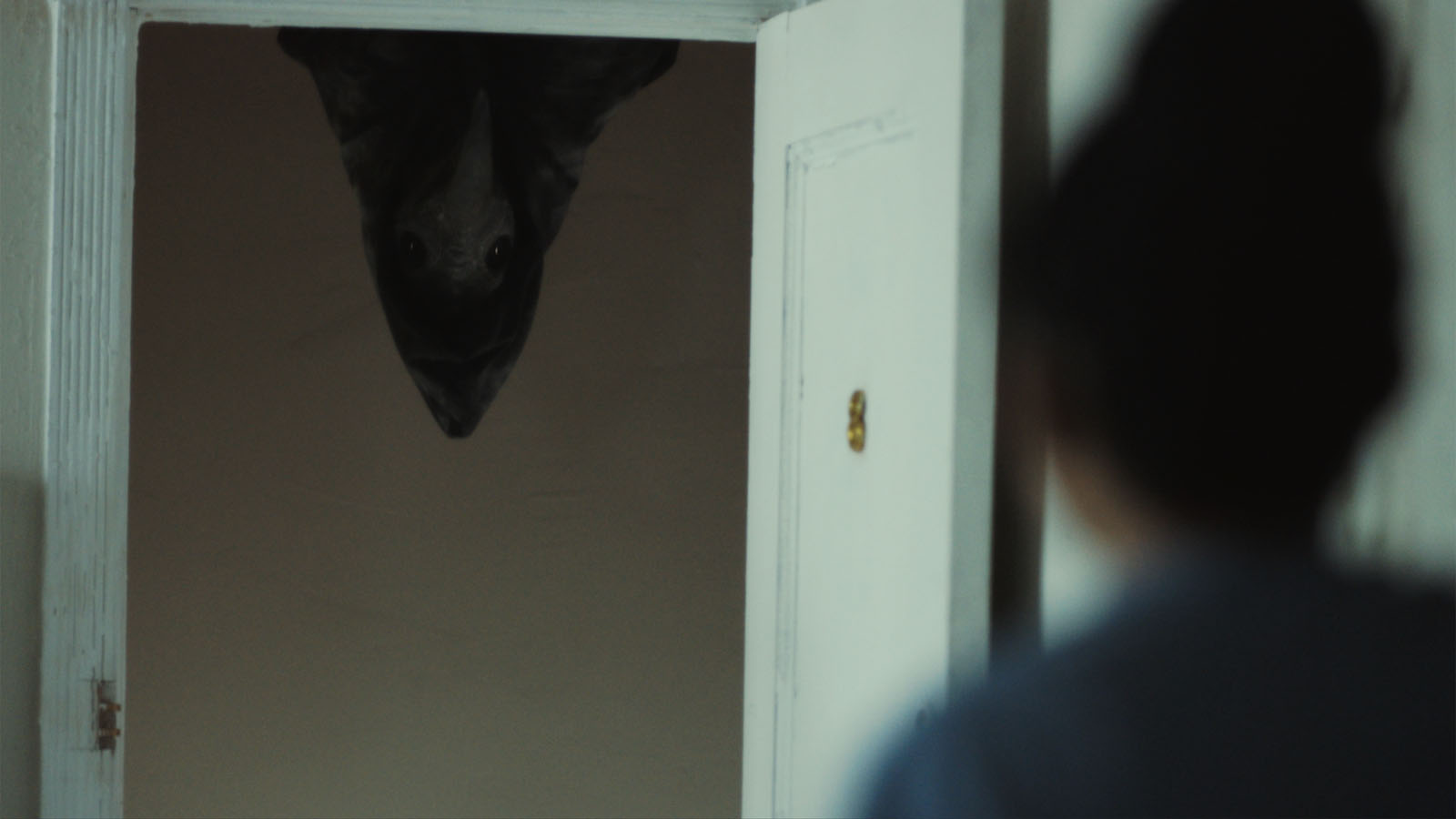

The stakes are elevated in The Harbinger because during COVID times, the concept of home is more sacred than ever. Mavis’s apartment, her quarantine zone, keeps her warm and sheltered, but it’s her dream life that torments her—she wouldn’t be safe anywhere. And the fact that Mitton chose the form of a plague doctor to personify the pandemic, and Mavis and Monique’s ghastly affliction, is nothing short of genius. This creepy-as-hell figure—a man adorned in a long coat and hat and a beak-like face mask historically worn to protect against infection while treating their plague-afflicted patients—represents quarantine, as these individuals were often forced into that state, and death. In the film, they’re also given the power to savagely erase a person from their family tree.

Blood relations factor heavily in Mitton’s universe, perhaps because his works are in part a family affair: Heisler, his wife, appears in three of his four features, and the demonologist’s children in The Harbinger are portrayed by her and Mitton’s own two kids. It is parent-child relations, though, that are most foundational to his films—namely, the playful banter and sometimes heartrending interactions between father and son in The Witch in the Window, the sister/brother/father triangle in The Harbinger, and, perhaps most memorably of all, the mother and son in We Go On (2016), terrifically played by Annette O’Toole and Clark Freeman. Their characters accidentally become a supernatural investigative team when the death-fearing son becomes so obsessed with the concept of the afterlife that he offers a cash prize to anyone who can present valid proof of its existence. Mom, worried after seeing his ad in the newspaper, decides to pay a surprise visit and ends up tagging along on his quest. When the first three candidates seem like a bust, he goes off on his own to visit a fourth, and more than finds what he’s looking for: he walks away with a dead guy’s ghost tethered to him. His super-protective mother, long burdened with secrets from the family’s past, steps up, prepared to do whatever it takes to extricate the awful spirit.

Images of this particularly repugnant ghost, the harbinger in plague-doctor guise, the old witch sitting too serenely in her chair, and an unsettling scarecrow figure in Mitton’s first feature YellowBrickRoad (2010)—which followed a group of expeditionists tracking the bizarre disappearance of an entire small New England town’s population, while also setting in motion the filmmaker’s “exploration” cinema of the unusual—effectively haunt viewers in all the best ways. But it’s not just this iconography, or even the spooky recurring sounds that lace the films’ soundtracks (the big-band music inexplicably playing in YellowBrickRoad’s woods, a child’s coughs from above in The Harbinger, the nighttime thumps of a cursed house in The Witch in the Window), that remain burned into your soul. The idea of being a prisoner of your own fears—not only of solitude or death, but, maybe more devastatingly, being forgotten entirely—is as terrifying and deeply crushing as anything supernatural. Mitton’s ability to blend these ingredients so effortlessly makes him one of the most transcendent filmmakers in modern horror, or any other genre for that matter. 🩸

is a writer, editor, and horror programmer based in New York. She is the editor of Bloodvine and her writing has appeared in publications such as The New York Times, Film Comment, and Rolling Stone.

Last night I watched myself sleep then I flew away, a young boy named Dalton...

BY NICHOLAS RUSSELL | Updated July 11, 2023

About a decade ago, an intriguing new contender stepped into the horror arena. It wasn’t so much a grandstanding moment as a quiet entrance from out of the blue, subtly sneaking into...

BY LAURA KERN | July 12, 2024

For no apparent reason, at the start of Rubber (2010), perhaps Quentin Dupieux’s best-known...

BY LAURA KERN | March 31, 2023

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021