Just about everyone loves Halloween—and if someone tells you they don’t, you might wish to keep your distance—but few people are aware of the spring’s variant on All Hallow’s Eve. That would be Walpurgis Night, which occurs in the ghostly interval between the close of the last day of April and the beginning of May. Christians offer prayers in honor of Saint Walpurga, an 8th-century abbess whose specialty is the warding off of witches, but as they say, you can only hold back a witch for so long, and it is on Walpurgis Night that these spell-casters take to their brooms, cats in tow.

Horror film fans may know that the plight of Renfield in 1931’s Dracula commences on Walpurgis Night, but the night very much belongs to the witches. As someone who wishes it could be October all year round, I like that this evening marks the midway point to Halloween, and I treat it similarly as an eldritch event — and that means watching a film steeped in the spirit of the occasion.

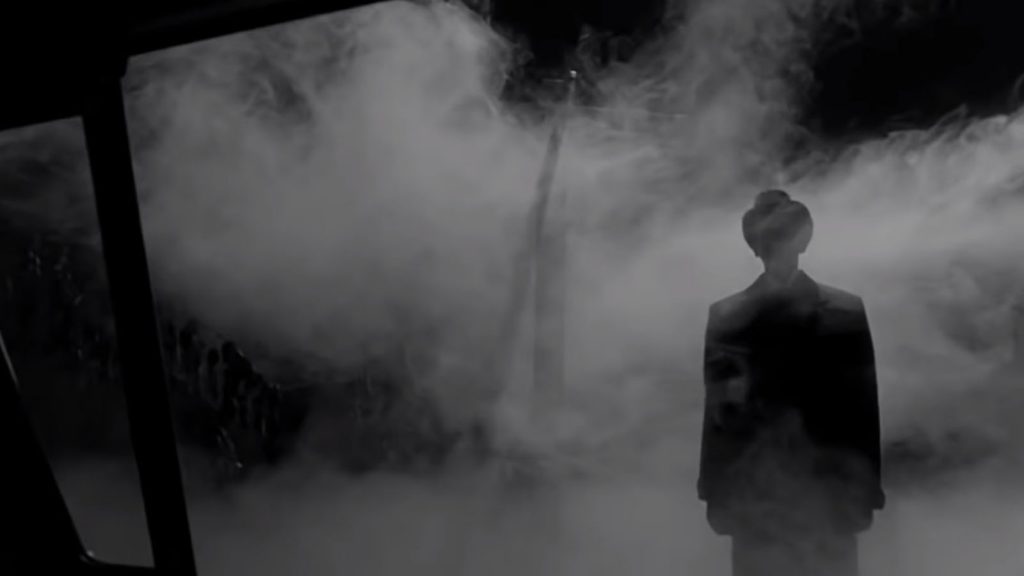

Little suits that purpose better than 1960’s The City of the Dead, the most fog-shrouded movie in cinema history, so much so that it’s a wonder you can even see any of the people—and the scores of witches—throughout. We are in the fictional Massachusetts town of Whitewood, first in 1692 for some witch-burning, and after in then-contemporary times for curses and bloodletting, witch-style, with a dollop of devil-worshiping.

Whitewood is clearly meant to be Salem, but the dodge is useful. It’s similar to Lovecraft’s utilization of Arkham, when he basically meant Salem as well — a certain dislocation from lore as we know it, with all of our relevant conceptions and the baggage of history, and instead this interstitial place where our imaginations have a bit more freedom to act against our steadiness of mind.

The City of the Dead stars Christopher Lee as Alan Driscoll, a history professor who is not only a history professor, because where would that leave our movie then? Put it this way: he sure knows a lot about witchcraft and has a fair amount of double duty going on in his life. He hangs out after class and engages in informal back-and-forth with gabby undergrads—shooting the shit about the deeper meanings of life as professors like this only seem to when they’re off the clock—while keeping an eye out for prospective recruits/sacrifices to the old Satanic cause.

Lee was one of those rare actors who had a remarkably long career and yet rarely dipped in his level of performance. Consistency served as his forte, aided by Lee’s naturally good taste in material. It wasn’t surprising later on to find him on camera reading the stories of M.R. James and advocating for the value of the ghost story writer’s work.

Like his frequent running mate Peter Cushing, Lee was pure class in a genre that was shedding some of its reputation—one that had been in place since the 1940s—as being primarily for kids. Adults thought that they couldn’t take horror seriously after the end of the initial Universal wave of films in the first half of the 1930s, when the novelty of the fright movie—in all of its newness—had people literally fainting in the aisles.

Quaint stuff now, but Lee represented grown-up, sophisticated horror, whether he was playing Dracula for Hammer in the late 1950s and giving the entire terror enterprise a dose of new blood by excelling at sucking out the old, or as the chthonic professor in The City of the Dead.

Hammer was a mix of splashy color and earth-tone saturation, the pictures possessing this forever-autumnal look, as if the various hues of dead tree leaves, forest paths, and exterior castle walls had leached further down into a canvas than they had ever gone before, taking hold of the viewer the way that a John Constable depiction of a heath could. Hammer red was never just red; it was either vermilion—a smoothed-over, but still torrid, former bubble of impasto—or a scumbled russet in which one could practically detect grains of earth.

The City of the Dead represents an inversion of the Hammer palette. The black-and-white photography is to the horror medium as that of 1947’s Out of the Past is to noir. It’s a film, like Robert Wise’s The Haunting a few years hence, in which the chiaroscuro patterns of contrast between somewhat light/dark/darker still/darkest-of-all act as a spectral character unto themselves—or a demonic bevy thereof.

We have here a British picture made with mostly British actors using American accents about this lore-steeped place in the States that we’re pretending is somewhere else. George Baxt wrote the treatment, with the original plan being that it’d make for a television series starring Boris Karloff, who would do Thriller instead. And while it wasn’t officially branded as such, The City of the Dead is the first Amicus production in all but name. Producer Milton Subotsky rewrote the Baxt draft, adding a boyfriend who heads off in search of his girl, and John Llewellyn Moxey was picked to direct what would be his debut.

Witch movies—and witch art—often involve pursuit. Witches get people moving. The witches of Macbeth send the Thane of Cawdor on his way. Hansel and Gretel are always in motion, as long as they’re not in an oven, so much so that they must leave a trail of breadcrumbs to return from where they had come. Witch horror films commonly have a mystery component, with a protagonist in the role of detective, to be followed by another character playing detective in search of the missing detective.

That’s what we get with the Val Lewton–produced 1943 picture The Seventh Victim (and the movie that pilfers so much from it, Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby a quarter of a century after) and 1973’s The Wicker Man—albeit minus an additional detective—with Christopher Lee doing something quite similar to what he does in The City of the Dead. In the latter, his Professor Driscoll character urges his precocious student Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson) to drive up the coast to Whitewood and experience some witch-based history firsthand—very firsthand, as it turns out.

From the moment of Nan’s arrival, awful augury abounds. If ever there was a place that said, “Turn the damn car around,” it would be Whitewood, which is less of a place and more of a fog bank that presumably has a layer of solid ground somewhere in there, though we often can’t see it. The City of the Dead is a spot-on title, and we needn’t fret that it gives too much away. In America, where subtlety itself often goes to die, the movie was retitled Horror Hotel, which completely misled the public as to what they were in for. An inn is central to the dreamlike, ghastly, ghostly action, but it’s an inn that a sea captain might have lodged at in 1797, not a Marriott.

The film is constantly disturbing. There are no comfortable moments once we get to Whitewood. The look of the place is accepted as if it were normal, and for this to be normal, unnatural order has to have taken over at the worst, or a lived-in, hypnagogic state at best. The City of the Dead is a nightmare that has elbowed reality aside, but almost without us knowing; that is, there’s no exposition as to how a place could both appear and be this way—it’s simply this possessed place.

To be noted about the dead: they always need new recruits. Apparently, witches do, too. The plot borrows from Robert Aickman’s 1955 story, “Ringing the Changes,” and would inform that of the 1977 children’s show—or at least that’s how it was pitched to the public—Children of the Stones. These witches have two lives: their living-lives and their dead-lives, and the twain meets in Whitewood. There is no line separating life from death once the town’s border is crossed. A place takes a hold of us and never leaves our thoughts, our memories; Whitewood, instead, attempts to take the whole of a person.

The film’s climax is one of those arrhythmia-producers—you feel like your heart may give out as the final action unfolds, much like in that first Hammer Dracula movie with Cushing and Lee in frenetic battle, the result being dependent on a cross—or the approximation of a cross. City of the Dead is a spiritually oppressive film, and a visually and physically oppressive one, too, which is no complaint. I can imagine director Moxey divvying up the budget by saying, “You know what? I’m going to spend 80 percent of this on fog machines.” You sense that your skin has gotten wet with the sea air while watching the movie. We never know how big this town is, because the fog distorts all, undercuts our sense of perspective and proportion. As a result, Whitewood’s graveyard resonates as the largest space we experience, a symbolic manifestation atop actual earth as to how readily the dead feed on the living. This isn’t zombie feeding; this is feasting upon the soul. In other words, the professor is playing for higher stakes than tenure.

Tom Naylor plays Bill Maitland, the second detective I had mentioned who sets off in search of the first, and here is also his fiancée. Sometimes a role like this would be added to a script so the boys in the theater could have someone identify with. They were there for the horror and the death and the fear, but it didn’t hurt to have an individual they could look up to on the screen and think, “Hey, that could be me!” The role can thus be a perfunctory add-on, but not so with The City of the Dead. Horror was largely fun in 1960. That would change over the decade. Is Night of the Living Dead fun? It’s awesome, and viewing it is a life experience, but providing fun isn’t what it’s about. The City of the Dead was one of the first horror films that transcended the idea of fun. It’s plain throughout, but the surprising ending—and the role of that fiancée in it—further attests that we’ve gotten a whole hell of a lot darker with the stifled dawn of this new decade.

As for the witches: despite the film’s outcome, you never acquire any peace of mind that they’ve been made to go away, or that the city will be allowed to die a natural death. That will be someone else’s problem, though, for just as witches seek recruits, there never seems to be an absence of them. Funny how that works. The dead city lives, and what a spell that requires—and what an effective imprecation we have in this movie. 🩸

is the author of eight books, including the story collection, If You [ ]: Fabula, Fantasy, F**kery, Hope, a 33 1/3 volume on Sam Cooke’s Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, Meatheads Say the Realest Things: A Satirical (Short) Novel of the Last Bro, and a book about 1951’s Scrooge as the ultimate horror film. His work has appeared in Harper’s, The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, The Daily Beast, Cineaste, Film Comment, Sight and Sound, JazzTimes, The New Yorker, The Guardian, and many other venues. He’s completing a book called And the Skin Was Gone: Essays on Works of Horror Art. His website is colinfleminglit.com, where he maintains the Many Moments More journal, which, at 2.7 million words and counting as of autumn 2023, is the longest sustained work of literature in history.

BY MICHAEL KORESKY | November 30, 2023

With his towering frame, regal bearing, and cruel blue eyes, Vincent Price stands tall in the pantheon of horror icons. But the prevalence of ham in his acting might suggest that he’s better suited to other holidays besides Halloween.

BY STEVEN MEARS | November 11, 2025

“On the rare occasion, a special child appears…” I first watched The Lords of Salem in an empty multiplex in Easton, PA, in 2013. After 10 minutes, I had to go ask them to turn off the lights. Two days later, I came back...

BY LAURA WYNNE | October 26, 2024

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021