Of the many recurring horror villains, Freddy Krueger is famously distinguished by his crispy face and razor claws, Jason Voorhees by his hockey mask and machete, and Leatherface by his human-flesh mask and chainsaw. They all have revenge or mental illness as their vague motivations to slaughter. But what does Predator bring to the horror-franchise table? Found beneath the creature’s space helmet is of course his ugly motherfucking face. This catchphrase descriptor runs throughout the series, and possessing a gross mouth with claws jutting out of each corner like insect mandibles—brilliantly designed by Stan Winston—he is certainly no beauty. But what is the Predator’s motivation beyond senseless bloodletting? Does it even matter? Slasher supervillains exist mainly to kill in nasty, crowd-pleasing ways, and Predator fulfills that mission, skinning people and keeping their skulls as trophies. It’s a flimsy jumping-off point to be sure, yet it’s effective enough to have spawned a fair number of films—now totaling five, or seven to those who choose to include the twin crossover-franchise Alien vs. Predator titles—as well as numerous video games, novelizations, and comic books, but this naturally just boils down to bankability and audience interest. And perhaps the strongest pull of the series is the top-tier talent it has consistently attracted, from directors to actors to crew members.

Predator lore goes that its concept came into existence through a Hollywood inside joke claiming that Rocky Balboa would soon need a superhuman opponent, since he’d vanquished all of Earth’s challengers. Adding to the mythology, Predator’s dreadlock-like quills adorning his head were inspired by a painting of a Rastafarian warrior that hung in producer Joel Silver’s office. Thus, a super-cool alien-being film premise (sans boxing) was born from the minds of brothers Jim and John Thomas, in their first script collaboration. At the time of Predator’s prepping, John McTiernan had made only one feature, the intriguing little supernatural thriller Nomads; this caught the attention of attached-star Arnold Schwarzenegger, who suggested that McTiernan be brought on to direct. It goes without saying that he proceeded to become a huge name in action movies, following up with one of the best of them all, Die Hard, but it was Predator (1987) raking in nearly $100 million from a budget of $18 million that most likely allowed for that to happen.

The shaky idea of blending the usual adrenaline-fueled Schwarzenegger fare with horror-soaked sci-fi was executed with surprising aplomb. Predator starts off as a candidate for the title of manliest action film, in a decade bursting with contenders. It’s all about muscles (and those with the biggest are the ones sporting vests), jeeps, helicopters, machine guns, cigars, and tough-talking. The testosterone practically drips from the screen. When the CIA agent played by Carl Weathers (a carryover from the Rocky franchise) first approaches Schwarzenegger’s super-tan special-ops soldier Dutch about leading a supposedly easy in-and-out mission to recover hostages in the scorching Guatemalan jungle, they can’t resist a quick arm-wrestle.

Though the film was generally well-received upon release, Predator’s magnified machismo held limited appeal to some. As a teenage girl, even with Commando and Total Recall making appearances on my film-still-collaged walls, I had little use for it, probably because it didn’t offer anything resembling the emotional father-daughter dynamic of Commando, or the kick-ass female power of Rachel Ticotin and Sharon Stone in Total Recall. But after repeatedly watching Dutch and his team carry on like they’re in a brawny action movie, only to discover they’re actually in a slasher film when they find three bodies hanging from the trees, I did finally come around to and even develop a serious soft spot for the film, which today many consider something of a classic and the strongest of the series.

Predator benefits from its spectacular setting and atmosphere: the moody jungle, with the soundtrack relying on the natural sounds of birds and monkeys, and a brazen, fully orchestral, militaristic action score by Alan Silvestri, whose work in the first two entries of the series was riffed on in various ways by other composers for later installments. The sole woman in the film (Elpidia Carrillo), and the only surviving hostage, warns the rescue team new to the jungle that they are in trouble. The locale soon becomes the stalking ground for the towering space monster (played by the seven-foot-two Kevin Peter Hall, replacing the originally cast Jean-Claude Van Damme after he was deemed too slight), whose perspective is shown via multicolored blobs of infrared and whose arrival is indicated by clicking noises—both exciting identifying factors of the series. (Voice actor Peter Cullen, known primarily as Transformers’s Optimus Prime, conceived of those clicks with horseshoe crabs in mind.) The initially invisible creature fades in and out like a hologram, in a kind-of-cheesy, kind-of-cool way, and picks off the characters one by one, building to a final showdown with Dutch.

Predator 2 (1990) relocates its action from the Central American jungle to the sweaty urban jungles of 1997 Los Angeles, during a horrific period of gang violence and drug wars, portrayed in wildly cartoonish fashion. Stephen Hopkins took the directing reins from McTiernan, and his work is especially sharp here (a warm-up perhaps for making the mini-classic man-vs.-beast survival flick The Ghost and the Darkness six years later). And as LAPD Lieutenant Mike Harrigan, an engaging, totally game Danny Glover fills the top spot in place of Schwarzenegger, who was in search of a better script and director, and more cash than what was being offered. (The actor has not been shy in expressing his discontent with the way the franchise has played out.) The strong supporting cast of the first film—Weathers, Bill Duke, Jesse Ventura, and Sonny Landham—is traded for a possibly even more stacked one here, featuring Gary Busey, Bill Paxton, Rubén Blades, and Robert Davi. Predator 2 again takes an already chaotic situation and adds in a murderous alien (a role reprised by Hall, though he died shortly after the film’s release, requiring other very tall men to take over in successive films), as well as some great set pieces in a graveyard and the subway, and culminates in what is essentially one long, exciting chase scene featuring Lt. Harrigan and the Predator. The film also sets in motion the idea that Predators follow a code for deciding who is worthy prey (María Conchita Alonso’s cop character is spared by the creature when it detects she is pregnant), and also that the Predator can talk (it finishes the line “You’re one ugly…” with “motherfucker”), and that the existence of multiple monsters is possible.

After the frostier critical and financial reception of part two, Predator went missing from the screen for 14 years, before reemerging for a pair of “Vs.” movies, a gimmicky conceit that a year earlier had introduced the (bad) idea of villains facing off with Freddy vs. Jason. Predator, rather obviously, was matched with Alien, the other horror-franchise entity from outer space. Alien devotees in particular discount these side-trajectory films, perhaps because the Xenomorph doesn’t exactly come across as the one to root for, but Alien vs. Predator (2004) is notable for Predator fans in that it provides the series with its first female lead. She’s no Ripley, but Sanaa Lathan’s take-charge environmental technician Alexa Woods, who is appointed the head of an elite team assembled to explore some unusual activity in the sub-Antarctic island of Bouvet—one of the most isolated (and alien-looking) places in the world—is a pretty damn welcome heroine. Written and directed by Paul W.S. Anderson, whose filmography reads like a sad list of video games, but who can never be fully disregarded because he once made Event Horizon, Alien vs. Predator is ambitious in scope if nothing else. And the sights of Lance Henriksen’s Charles Bishop Weyland spearheading the expedition, the two iconic space creatures standing face to face—even if there’s admittedly not enough dueling in either Alien vs. Predator or Alien vs. Predator: Requiem (2007)—and, most of all, an alien breaking out of a predator’s stomach are all undeniably satisfying. Featuring the weakest cast of the Predator films but some of the best gore, Requiem, directed by noted visual-effects artists Colin and Greg Strause (credited as The Brothers Strause), is mostly set in the darkness of rural Colorado, the new battleground destination for the two alien species, notoriously rendering some of the action indistinguishable. Even making out which type of creature is present in certain scenes feels impossible.

With 2010’s Predators, we finally got the first of the sci-fi series to be set entirely in space—even if the characters don’t immediately know it. The film intriguingly begins with a man (Adrien Brody) free-falling from the sky, desperately fighting to get to his parachute open. Other cast luminaries follow (Danny Trejo, Alice Braga, Mahershala Ali). The jungle terrain they land in is unlike any they’ve ever seen, because, as it turns out, it’s not a planet they’ve ever visited. This time, a blatant Most Dangerous Game scenario is enacted, with the Predators bringing their hunt—a chosen group of people with criminal backgrounds (read: monsters themselves)—to their personal game preserve. Director Nimród Antal is a supremely talented filmmaker I’ve been championing for years, and though we’d all benefit from having him doing something less routine than a Predator movie, his contribution to the series seems to get better with each viewing. It does, after all, feature Laurence Fishburne as a survivor in hiding who lets the group know what they’re up against (creatures with one purpose: to make themselves better killers); a Predator-vs.-Predator clash (there are two rivaling varieties here); and a silly-but-fun yakuza-style fight, pitting claws against sword in the tall grass. And the dynamic between Brody’s mercenary and Braga’s sniper introduces the closest thing to a romance that the series has yet seen. The film also pays homage to the franchise’s roots by playing Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” over the end credits, a song featured early on in Predator.

Writer-director Shane Black—a cast member of the original Predator, and amusingly the first of the creature’s victims—attempted his own brand of reinvention years later with The Predator (2018). His script (co-written with Fred Dekker) is the only one of the main franchise credited to its director, but unfortunately his usual clever humor doesn’t mix so well with sci-fi horror. Black’s is the most tongue-in-cheek Predator film—he probably should have put the “Predator” of the title in quotes, because there’s a running joke that the creature is in fact ill-defined as a predator and is more accurately a sport hunter—but he does at least speed up the pace, with the title character wreaking bloody havoc faster than usual. This time, he lands his pod in Mexico right in the middle of a military operation led by a sniper (Boyd Holbrook), before being captured and brought to the U.S. for observation. The sniper, some fellow damaged soldiers, and a scientist (Olivia Munn) work together to find him after he escapes. Black’s evolved, possibly hybridized, version of the creature, aware of climate change and the concept of humans being an endangered species, has now graduated to being called “one beautiful motherfucker.”

At this point, Predator fatigue had widely set in. So when a new iteration was announced, it seemed destined to disappoint. But with Dan Trachtenberg at the helm, there were still pangs of hope. His stellar 2016 debut feature, 10 Cloverfield Lane, craftily carried forward a franchise in the making, and he brings the same smarts to Prey. Soon after it dropped on Hulu, the film had broken all of the streaming service’s viewership-number records, and its many rabid fans are rightly up in arms that it’s been robbed of the big-screen treatment. (It is admittedly depressing to see the glorious 20th Century Fox logo that opens all of the Predator films—or “20th Century Studios,” as it’s now called—appear on a movie relegated to an at-home release.)

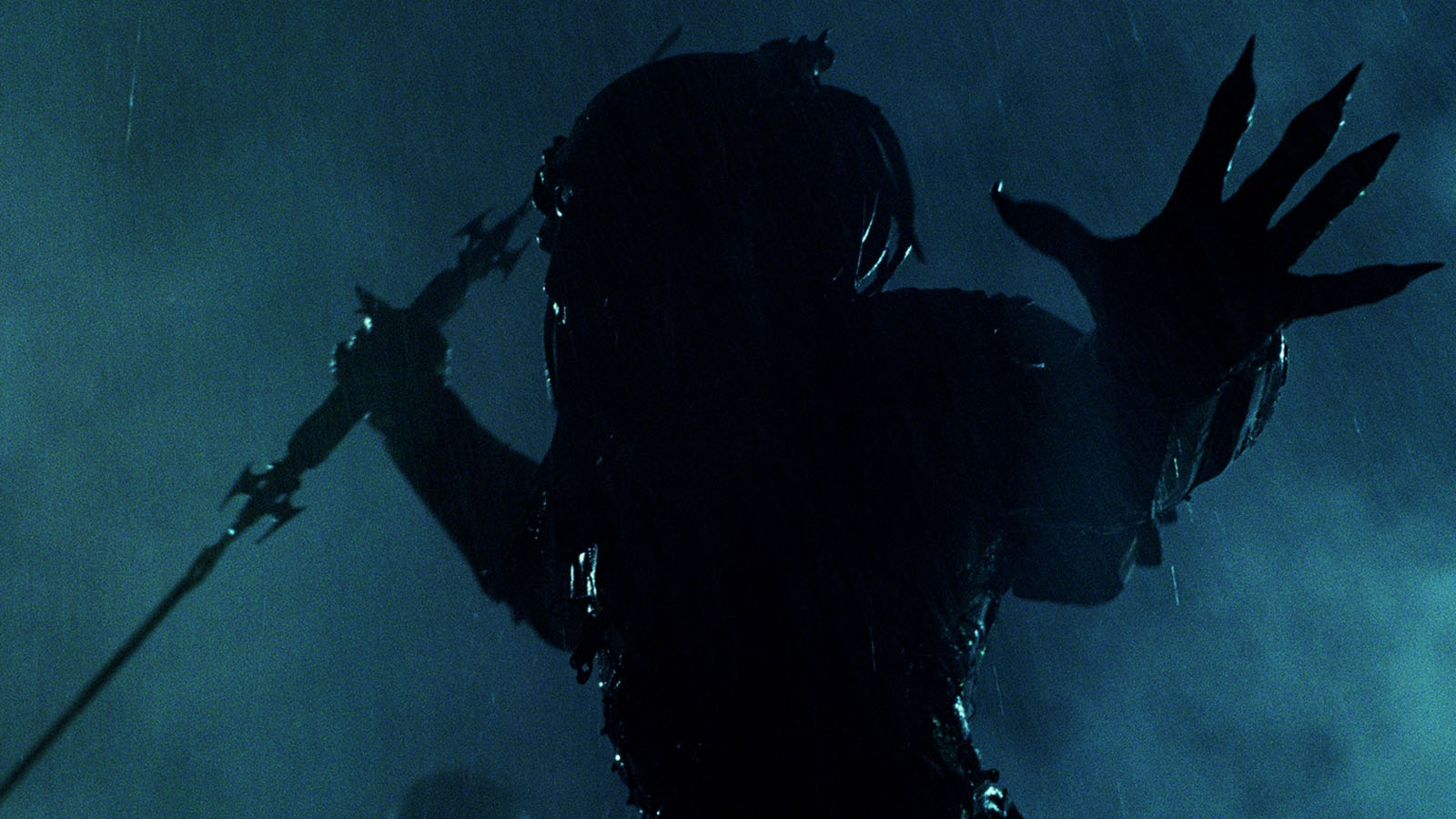

The prequel, set in the Northern Great Plains of 1719, is so successful because Trachtenberg and screenwriter Patrick Aison essentially chose to strip the whole thing bare in order to bring the series back to the basics of the original film. Here, there’s one clear main character, the most strikingly sympathetic of the entire series, who also just happens to be its first bona fide woman hero to hold the majority of screen time; even as a creature origin story, it makes sense that for once the title refers to the human cast and not the monster. For simplicity’s sake, there’s also only one monster, a more primitive-looking variation, who’s learning to become a master hunter at the same time as Naru (a wonderful Amber Midthunder), the feisty Comanche woman with mad tracking and tomahawk skills determined to prove herself as adept as the small-minded men who think she’s better suited to be a cook. She is of course the most capable of them all: she’s the sole person to glimpse the Predator’s arriving spaceship, and the first to see the slowly materializing form of the massive creature. But no one will believe her that there’s a larger threat in town than the bear and tiger that have been coming around. Once Predator starts skinning animals and killing off the reservation’s people, Naru’s brother repeats a famous line said by Schwarzenegger’s Dutch in the first Predator: “If it bleeds, we can kill it.” There are no surprises as to who actually pulls off that feat.

Lots of bullshit talk has been spouted about Prey being so “woke”—the worst neologism of the modern era—but nobody could argue that the Predator series wasn’t inclusive from day one, with Black, Latina, and Native American actors in the original film and racially diverse casts appearing consistently thereafter. But Prey is notable for being the first Hollywood franchise film to feature exclusively Native American roles (save for Predator itself), and also for sticking to its practical-effects roots by using a real person as the creature—though to me, and apparently some others, the added use of CGI is more egregious here, especially in the case of the animals. But the choice to focus so heavily on the simple pleasures of Predator’s clicking sounds, infrared views, and glowing light-green blood-slime was a wise one indeed. Prey has performed vital resuscitation on a franchise that was barely breathing. Groans of “oh no, not another one” have morphed into thirsting for more of the series, and specifically of Naru and her adorable dog, too. 🩸

is a writer, editor, and horror programmer based in New York. She is the editor of Bloodvine and her writing has appeared in publications such as The New York Times, Film Comment, and Rolling Stone.

High-concept, no-frills horror is writer-director-editor-composer Andy Mitton’s modus operandi. While his four features (the first two co-directed with Jesse Holland) address vaster subjects of death and the afterlife...

BY LAURA KERN | December 5, 2022

Last night I watched myself sleep then I flew away, a young boy named Dalton writes in crayon shortly before his spirit leaves his physical body and becomes prey...

BY NICHOLAS RUSSELL | Updated July 11, 2023

A horde of diabolical children have preceded Esther of Orphan (2009), directed by Jaume Collet-Serra, but she has secured a place among horror cinema’s most memorable enfants terribles, even before its long-awaited prequel, Orphan: First Kill, arrived last year.

BY KELLI WESTON | April 28, 2023

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021