Christmas: a dream for some, a nightmare for others, and conceivably either for each of us, depending upon the time in life. Undertake an observant outing during the Christmas season, and you get a strong indication of where you’re at, as if you didn’t know. Observing a happy family in a café can make you feel like all is sometimes gotten right, at least somewhere in the world, in similar fashion to your portion of it, or it can cause you to feel alone or frightened. Sometimes we sit and watch a while, and in other instances, we must up and leave.

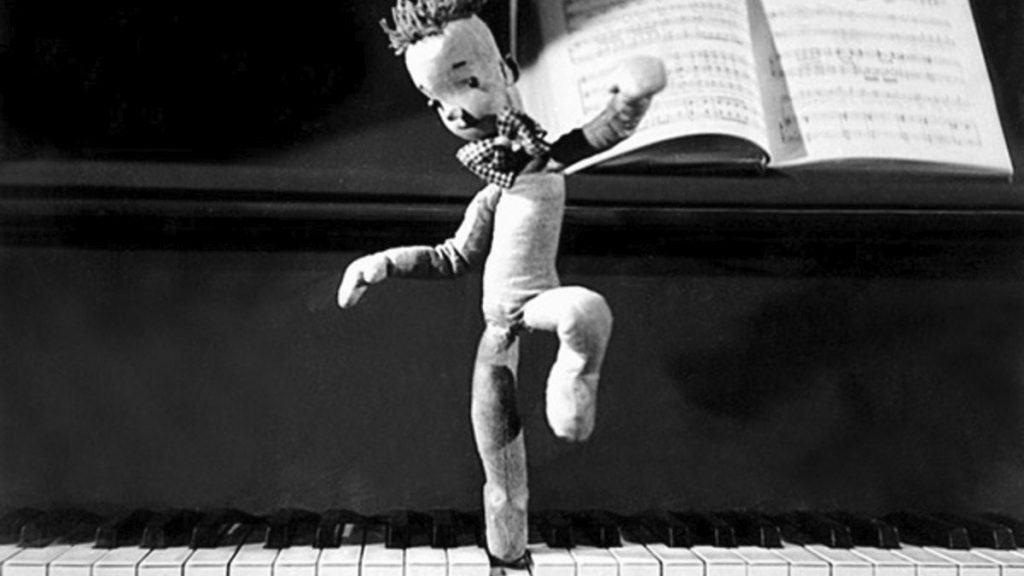

Bořivoj and Karel Zeman’s 1945 Czechoslovakian stop-motion short film A Christmas Dream is about a rag doll whose stint as a favorite toy has passed. The little girl who owns him has moved on in anticipation of what she’ll receive for the Christmas that’s about to come. But the boy rag doll says, “Not so fast, child!” and attempts to win her back with a dazzling show: he’ll will himself to life, as well as his other cohorts—like a giraffe, whom he rides as if it were his pacing stead—scattered about the room.

The idea of toys becoming alive is fraught with metaphor. As Charlie Brown noted, consumption itself consumes us during the Christmas season, such that we can lose sight of what it’s supposed to be about. Goodwill to man—which means everyone—and all that Vince Guaraldi jazz. Toys shouldn’t be the life of the Christmas party in the holiday’s grand scheme.

A Christmas Dream is a film that can go a couple of ways. Either it soothes your festal soul—a cinematic version of dancing sugar plum visions—or it disturbs you. The girl’s dream is remarkably “awake.” Real. There’s a tactility to this experience. A dream with wakefulness—it’s Christmas, when such things are possible. And danger as well.

The rag doll is willing to risk his life—there’s a deadly fan, for instance—just to impress this child. He’s both the lord of the dance and a performing, unpaid employee. She seems pleased—a slumbering tyke analogue for Clara in the second act of The Nutcracker—but we know how life can be for a toy and that a child’s love isn’t forever. The best a toy might hope for—and, come to think of it, many of us—is to be a pleasant memory sometime later for someone else. Allowing that you weren’t thrown away and destroyed.

Creatures that ought to be inanimate but dance around a child’s bed are naturally suggestive of horror. This isn’t a wealthy family. Their tree is a real straggler with spindly branches that look like bony fingers. We aren’t so much scared as knocked off-kilter by a lived-in, emotional Christmas space.

Think of A Christmas Dream as the oneiric stop-motion cousin of the Val Lewton–produced The Curse of the Cat People from the year before. In that picture, a lonely girl either conjures or is visited by a friend from the beyond. We’re never sure which. Again, there’s that off-kiltering effect. We’re put on our sides and made to view the world—and what Christmas reveals about it—from a different angle, with virtuosic, legato, and, yes, dreamlike smoothness and clarity.

It’s strange what can give us nightmares. The Heat Miser in Rankin/Bass’s The Year Without a Santa Claus, for example, and he’s meant to be funny. Or Santa in the flesh. Had you ventured downstairs and witnessed a jolly, rotund elf come barreling down your chimney, you’d likely have fled back to your room, rather than stand there in silent fascination, observing this fellow’s every movement until he touched a finger to his nose and shot himself back up to your roof. That would be traumatizing. Who’d believe you? And remember: we must believe survivors.

But thankfully, Santa has a way of making these midnight creeps of his work—for many, if not all. There are the who’s been naughty and who’s been nice lists that get the brunt of the hype this time of year, but, alas, in this world, there’s a different, overarching manner of record, and that’s the haves and have-nots. A parent of a child who wants for things they rarely get will desire to look away from A Christmas Dream (or “wake” from it). And perhaps the parent who spoils their kids for a form of clout in their particular social circle could be spooked into a degree of shame. A reminder that the gift of kindness never gets old or expires or is left out on the curb to be replaced a few Christmases later by something better.

Or it could be that this Christmas film makes us think about these ideas, and that is your fright factor. We block out so much—and refuse to think or fear thinking—as we race here, race there, make sure this package is delivered on time or that image from the kids’ school Christmas concert is posted at a particular hour for max visibility on our socials. What if you’re doing Christmas wrong, for all the ballyhoo? What if you feel nothing in your heart for this time of year, and for others, save relief when it’s over? Christmas dreams, Christmas nightmares. Sometimes they’re closer to each other than we wish. 🩸

is the author of eight books, including the story collection, If You [ ]: Fabula, Fantasy, F**kery, Hope, a 33 1/3 volume on Sam Cooke’s Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, Meatheads Say the Realest Things: A Satirical (Short) Novel of the Last Bro, and a book about 1951’s Scrooge as the ultimate horror film. His work has appeared in Harper’s, The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, The Daily Beast, Cineaste, Film Comment, Sight and Sound, JazzTimes, The New Yorker, The Guardian, and many other venues. He’s completing a book called And the Skin Was Gone: Essays on Works of Horror Art. His website is colinfleminglit.com, where he maintains the Many Moments More journal, which, at 2.7 million words and counting as of autumn 2023, is the longest sustained work of literature in history.

BY COLIN FLEMING | October 31, 2025

On Christmas 1950, Judy Garland reprised her role as Dorothy for a Lux Radio Theatre broadcast of The Wizard of Oz. One wonders what this must have been like for her.

BY COLIN FLEMING | December 29, 2025

Blue Beard is a glutton. He likes food and female orifices, in that order, which doesn’t mean he doesn’t have a major thing for the latter in this early 1901 French-film dazzler by Georges Méliès.

BY COLIN FLEMING | February 16, 2025

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021