On Christmas 1950, Judy Garland reprised her role as Dorothy for a Lux Radio Theatre broadcast of The Wizard of Oz. One wonders what this must have been like for her. When she’d last found herself wearing those ruby slippers, she was a teenager under enormous pressure. Her life had been hard and continued to be hard, and now here she was again as an adult, with her daughter Liza in tow, melting a witch down to a puddle and making it back home. Again. A couple of ways over.

The Wizard of Oz is the Christmas movie that wasn’t, much like it’s a horror movie that isn’t. It has long played on television on Christmas Day, and we can only guess at the number of people—and families—for whom watching it is part of their 12/25 tradition.

Why does The Wizard of Oz feel like a Christmas film? It’s magic-laden. And we’re not talking about the legerdemain prowess of the Wizard himself. Christmas is a time of magic. When a cold, still night, on one of the shortest days of the year, may feel charged with the possibility of worlds that don’t normally overlap doing just that to the person able and willing to let go of what they think they know, and…venture. And bear witness to visiting spirits. The best art is itself magical. That doesn’t mean sorcerers and dragons. We’re talking that which is beyond our world, and that shines a light on it nonetheless. You could say, because of.

There isn’t a more magical movie than The Wizard of Oz, and there isn’t a more magical day than Christmas. So there you have it. As for horror: who has ever watched The Wizard of Oz and failed to find themselves terrified during portions of it? Just as It’s a Wonderful Life contains the scariest horror film of the 1940s, The Wizard of Oz features a cadre of moments that constitute the stuff of some of our earliest screen-related nightmares, with Victor Fleming going full (imaginative) throttle, a director unwilling to stint on scares.

They begin early with the potential murder of the little dog Toto, courtesy of the dreaded Miss Almira Gulch (Margaret Hamilton, who’s going to play another part here soon enough). Did you ever have a neighbor whose visage in a window made you want to run back to the safety of your yard? Have you ever forgotten their silhouette?

Then we have Dorothy trapped outside, alone, as a deadly storm kicks up. She could die, her family could die. Seemingly seconds later, she’s in an empty house that is ripped off of the ground and tossed through the air en route to obliteration, but instead happens to land on a witch, which triggers the appearance of the ultimate wicked witch.

If you’re of a certain age, this is when you first want to hide under your seat. Come to think of it, you can be any age. Dorothy is a young girl far from home. A home that may no longer exist. With probably no way of getting back. And you thought your first day at a new school was hard.

But our fear journey has just begun. That fear will be offset by friendship, loyalty, and love. Kind of sounds like life, doesn’t it? If we’re lucky. Dorothy is blessed with friends in Oz and is also a true friend herself. The Yellow Brick Road—which looks so bright and beckoning at first—has a knack for turning menacing. The sparkle fades. Shadows darken it. Weeds grow in cracks. Are we still going the right way? The trees come alive—but not always, just in spots.

For all its color, darkness is present throughout The Wizard of Oz. At Christmastime, we tell ghost stories. Or we once did. Some still do. The curtain between worlds isn’t as thick as normal. It has some give. You can push a hand into a different time, place, or plane, while the veil remains against your skin. The same as we feel like we’re leaving a world behind—as part of an elongated crossing over—the further Dorothy gets from the house that killed a witch.

There’s a field of poppies that drug our heroes, making them even more vulnerable to the Wicked Witch of the West. We’re defenseless as we sleep, and it isn’t as if self-preservation was easy to come by when Dorothy and her tin man, scarecrow, and lion friends had their wits and faculties about them. The flying monkeys of death—like, what the hell—are fear itself distilled into cinema. Would we allow their inclusion in a “children’s” film in the 21st century? Are they only permissible in this work from the year of Lou Gehrig’s “Luckiest man on the face of the earth” speech because they’ve in effect been grandfathered into our here and now by a television broadcast rights package?

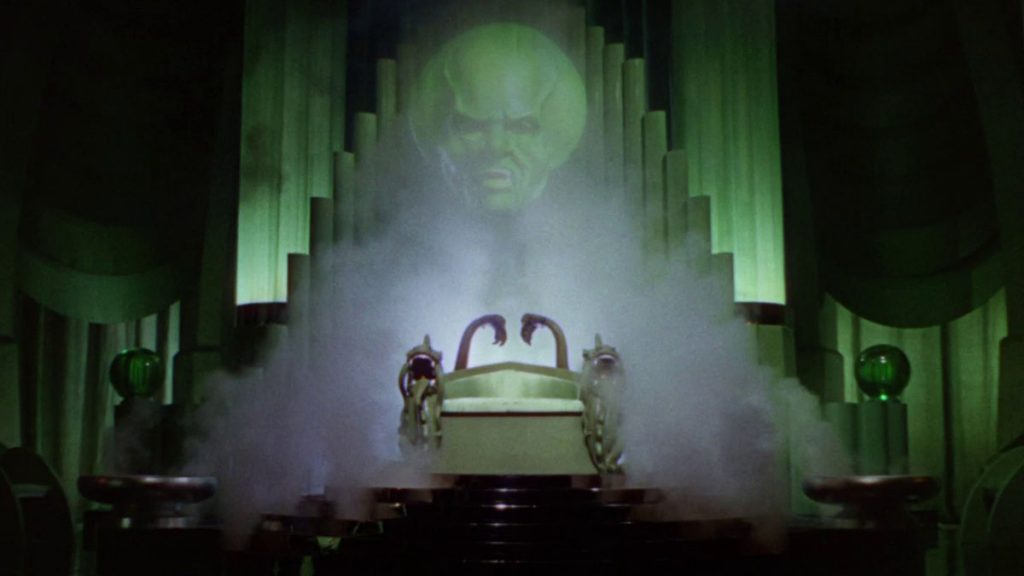

The workers who do the bidding of the witch at her castle suggest the Szgany beholden to Dracula at his, but with a work song that never leaves the darkest province of your mind’s inner ear. Nor is the Wizard—at first—a calming presence. That he wants what’s tantamount to a trophy earned by killing—the Wicked Witch’s broom—tracks with all that we’ve experienced to date. And there’s so much fire in this movie. Can you conceive of the pain of being burnt alive? The melting of flesh. Eat your popcorn, kiddies.

The Wizard of Oz is truly seminal modern movie horror. The seed and the root. It’s so frightening that it needn’t be termed horror. You know it when you see it, and you definitely know it when you feel it. This is a nightmare in film form, albeit one alleviated by connections, kindness, hope, and the idea and sanctity of home, when home and heart intertwine. The same as The Wizard of Oz, Christmas, and our world when we watch the one on the day of the other. 🩸

is the author of eight books, including the story collection, If You [ ]: Fabula, Fantasy, F**kery, Hope, a 33 1/3 volume on Sam Cooke’s Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, Meatheads Say the Realest Things: A Satirical (Short) Novel of the Last Bro, and a book about 1951’s Scrooge as the ultimate horror film. His work has appeared in Harper’s, The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, The Daily Beast, Cineaste, Film Comment, Sight and Sound, JazzTimes, The New Yorker, The Guardian, and many other venues. He’s completing a book called And the Skin Was Gone: Essays on Works of Horror Art. His website is colinfleminglit.com, where he maintains the Many Moments More journal, which, at 2.7 million words and counting as of autumn 2023, is the longest sustained work of literature in history.

With his towering frame, regal bearing, and cruel blue eyes, Vincent Price stands tall in the pantheon of horror icons. But the prevalence of ham in his acting might suggest that he’s better suited to other holidays besides Halloween.

BY STEVEN MEARS | November 11, 2025

BY MICHAEL KORESKY | November 30, 2023

“On the rare occasion, a special child appears…” I first watched The Lords of Salem in an empty multiplex in Easton, PA, in 2013. After 10 minutes, I had to go ask them to turn off the lights. Two days later, I came back...

BY LAURA WYNNE | October 26, 2024

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021