You can lose everything else, but you can’t lose your talent,” proclaims “Baby” Jane Hudson (Bette Davis), a former child star plotting a doomed comeback. Robert Aldrich’s 1962 “Grande Dame Guignol” masterpiece What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was hardly the first film to employ the services of A-list actors in horror roles—a practice often seen as an exchange of legitimacy for quick cash—but its runaway box-office success and resultant Oscar nomination for Davis launched a cycle of chillers headlined by aging, top-tier performers. Baby Jane’s spiritual sequel Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), and The Shining (1980) number among the horror classics that challenged their venerated stars and rewarded them in kind. Here we’ll consider those entries’ less prestigious cousins.

My aim is not to further the myth that, in line with Baby Jane’s quote, great actors who turn their attention to horror late in life must have lost everything but their talent. Embracing the dark arts in the back half of an esteemed career is by no means an act of self-abasement. Indeed, Ruth Gordon was a screenwriter and character actress of long standing, but not a household name until she served Mia Farrow’s Rosemary the fateful mousse with the chalky under-taste; clutching her Oscar statuette, the septuagenarian breakout star quipped, “I can’t tell you how encouraging a thing like this is!”

While awards and horror movies seldom keep company, past award-winners are invaluable to the genre, their dignity and professionalism elevating outlandish plots. That’s certainly the case with George McCowan’s 1972 eco-thriller Frogs, starring Ray Milland more than a quarter-century after he won the Best Actor Oscar for The Lost Weekend (1945). His primary function in Frogs is to class up the proceedings, and the producers got their money’s worth. He plays Jason Crockett, the irascible and iron-willed patriarch of a family of Florida tycoons. If there’s anything the Crocketts hate more than the safety regulations their factories are forced to comply with, it’s the wildlife teeming on their island estate, blasted with poison but inexplicably gaining in number. Amphibious sounds practically score the film, with ubiquitous trills and gurgles portending the hostility of the environment from the very first scene.

While the clear antecedent of Frogs is Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), the Crocketts’ Southern-fried avarice and infighting (and obsession with bygone athletic records) suggest a genre-inflected Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, with Milland’s Jason a surrogate Big Daddy. Wheelchair-bound but ruthless, swigging double old-fashioneds and adorning his home with taxidermied beasts, he’s determined that nothing—not even nature’s fury—will interfere with the family’s celebration of his birthday on the Fourth of July. As proof of his cold-bloodedness, he shoots a snake out of a chandelier and speaks loftily of man’s role as master of the universe, entitled to destroy whatever troubles him. A clean-shaven, 27-year-old Sam Elliott plays his moral adversary, a wildlife photographer who advocates for harmony among all creatures.

Welsh-born Milland had dabbled in horror before, notably in the 1944 haunted-house touchstone The Uninvited and a low-budget pair for Roger Corman, Premature Burial (1962) and X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963). Even his most famous role, the alcoholic writer in The Lost Weekend, is presented with some of the trappings of horror cinema (especially his detox-inspired hallucination of a bat killing a mouse, with the rodent’s blood trickling down a wall); in Alias Nick Beal (1949), a noirish update of Faust, he literally plays the devil. In Frogs, he’s ever-present in his chair, an immobile but indomitable sentry. As marshland denizens overrun the estate (not just snakes and frogs in Biblical quantities, but gators, tarantulas, and obviously superimposed birds), Jason brooks no dissent. We’re not told why this annual celebration is so important to the eldest Crockett that he dismisses the rising body count, but it’s clear that he’s a man accustomed to deciding when debates are over.

Milland brings a touch of wry humor and succulent ham to his portrayal, talking out of one side of his mouth and muzzling panic-stricken relatives with disgusted rejoinders (though there’s never any doubt that he, like his nemeses, will croak). The ecological message is hard to take seriously when toads are hopping onto the birthday cake and Elliott is repeatedly stripping to the waist like a sun-dried proto-McConaughey, but Milland provides the film’s missing ingredients: grit and gravitas. His movie-star authority makes you stop asking yourself what lizards native to Argentina are doing in a Florida swamp, and instead imagine for 90 minutes that you’re watching a version of King Lear—albeit one with marauding frogs.

The Devil’s Rain (1975), by British journeyman Robert Fuest (best remembered for The Abominable Dr. Phibes), is every bit as silly as its title implies, but as the diabolically charismatic head of a cult of devil worshippers, Ernest Borgnine exhibits such deranged glee that one suspects the husky, gap-toothed star had waited all his life to sport a red velvet robe and ram’s horns. The Oscar-winner for Marty (1955) had played his share of loathsome villains (in From Here to Eternity, Bad Day at Black Rock, and Aldrich’s underrated Emperor of the North Pole), but in his performance as Jonathan Corbis, ageless Mephistophelian priest and keeper of souls in a glass bottle, he casts off all vestiges of restraint, making the film a must for fans of hellfire histrionics.

The four-pronged aptness of calling The Devil’s Rain a cult movie is pithily explained by Australian critic and bad-movie aficionado Michael Adams: “It’s about a cult, has a cult following, was devised with input from a cult leader [Satanist Anton LaVey, a technical advisor and supporting actor], and saw a future superstar indoctrinated into a cult he’d help popularize [John Travolta, making his feature debut, received a copy of the Scientology bible Dianetics during production].” The film finds William Shatner and Tom Skerritt as brothers descended from a 17th-century Puritan (Shatner again) who betrayed Corbis (Borgnine in Pilgrim garb); now they must destroy the bottle of lost souls, which will unleash the titular rain that melts onlookers’ flesh like wax candles. Or something like that.

The key to playing these roles is knowing how much distance to place between yourself and the character, and Borgnine rightly opts for a gap of nary an inch. Faux friendliness and a hearty laugh are his most effective tools, outwardly disarming but profoundly unnerving. His bulging eyes shimmer as he intones cheerfully, “Didst one of thee fall from the favor of Lucifer?,” and when he tries to tempt Shatner with “Lilith, queen of delights,” he speaks with the same licentious relish apparent in the 2008 Fox & Friends clip that went viral when the 91-year-old screen legend shared the secret to his own longevity.

An actor who could conjure an unwholesome aura just by flashing his satyr’s grin, the beetle-browed Borgnine easily surpasses Shatner’s theatrics and Skerritt’s ramrod stiffness. (Fifteen years earlier, Charlton Heston and John Gavin might’ve played the brothers in exactly the same register.) Classic Hollywood stalwarts Ida Lupino, Keenan Wynn, and Eddie Albert appear in small roles that are markedly enriched by their efforts. But up until the climactic sequence in which the entire cast twists and moans in agony like figures in the last panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s painting The Garden of Earthly Delights, which the camera surveys Ken Burns–style in the opening credits, it’s Borgnine’s show. Hell hath no fury like a scene-stealer unleashed.

Would that Veronica Lake had heeded that lesson in Flesh Feast (1970), it might not stand as the unworthiest swan song ever afforded a Golden Age icon. Helmed by Brad F. Grinter, who later directed 1972’s Blood Freak (the Vietnam-era Reefer Madness update with turkey-headed cannibals the world had been clamoring for), Flesh Feast regards the comparably restrained efforts of Dr. Elaine Frederick (Lake, two years before her untimely death at 50) to refine a process wherein ravenous maggots attack and regenerate decaying skin. It goes without saying that South American revolutionaries are using this method to revive Hitler (successfully), but it might surprise one or two viewers that Dr. Frederick’s true motive is revenge, since her mother died in a concentration camp as a guinea pig for this same treatment. And they say Hollywood is out of ideas.

Lake, who supplied one of the war years’ most appealing heroines in Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels (1941), but whose peekaboo hairstyle and troubled private life (which could inspire a Frances-like biopic) eclipsed her career in the public consciousness, co-financed Flesh Feast with the proceeds from her memoir. It was filmed in Florida (like Frogs) with hapless regional actors, and while Lake at least achieves competency, she appears to have received no direction from Grinter, since her line readings lack the necessary tongue-in-cheek humor (of which she was demonstrably capable). Poor ADR may be partly to blame for this; there’s so much dubbing that the characters seem to be talking past one another.

Still elegant but revealing the toll of the years, Lake is left alone to reconcile the paradox of her first intellectual role being also her most cloddishly written. Her voice is often coarse, and occasionally reaches an agitated rasp; the most that can be said for the first hour of the 72-minute runtime is that she asserts unwavering conviction amid incoherent plotting, static blocking, and arbitrary compositions. What little camp value exists, in a work that by rights should be much more fun, is confined to the last few scenes, in which she settles scores with a Mel Brooks–worthy caricature of the resuscitated Führer (“I had nussing to do vith it! It vas Eichmann und Goebbels!”). “What’s the matter? Don’t you like my little maggots?” she cackles as she hurls the larvae in his face (which, if I understand the scenario, should rejuvenate it). The last words spoken on-screen by Veronica Lake are a sardonic “Heil Hitler!,” and, tragically, it must be concluded that her valedictory film offered her nothing but exploitation and witless degradation. She deserved better, and so do we.

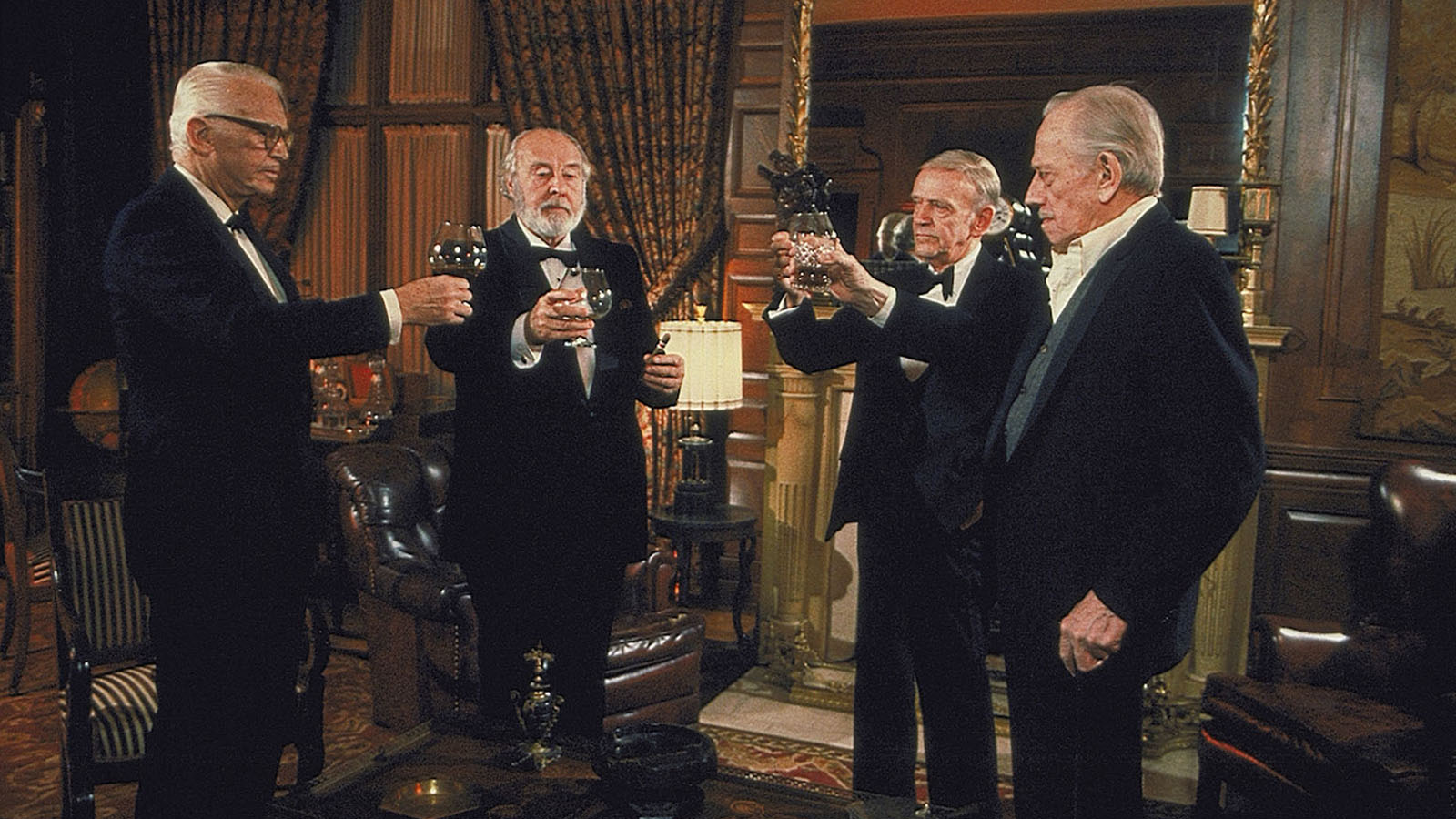

By and large we get it in Ghost Story (1981), directed by John Irvin, fresh from his landmark BBC adaptation of John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979). Having elicited a career performance from Alec Guinness in that miniseries, he sought to quadruple his dividends in this multigenerational suspenser, the last big-screen outing for Fred Astaire, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Melvyn Douglas (who had just appeared alongside George C. Scott in another horror film with a blue-chip cast, 1980’s The Changeling). John Houseman rounds out the Chowder Society, a quartet of elderly New Englanders who meet frequently to swap tales of the supernatural over cigars and brandy, and to wallow in their lifelong guilt over the woman whom they accidently sent to a watery grave in their youths. Meanwhile, Fairbanks’s sons (both played by Craig Wasson) are beguiled by her vengeance-seeking apparition (the spectral and seductive Alice Krige).

Astaire, Fairbanks, and Douglas look smaller and more fragile than they’d ever appeared before; even the bluff Houseman has moments of startling vulnerability. Whatever the screenplay’s deficiencies, it deserves credit for presenting four eightyish characters who are forced to confront their mortality, and entrusting them to actors well-remembered as lithe and virile, but now unmistakably in their dotage. Douglas in particular plays against type as a man so encumbered by the burden of one misdeed that now, half a century later, he lives on the brink of tears. (Poignantly, the double Oscar-winner died before the film’s release.)

Ghost Story is essentially a thoughtful and serious work, tricked out with jump-scares and moments of luridness (as when Wasson falls fully nude out a window, sharply downward and through another pane of glass into a swimming complex). These superfluous asides made me hate the film when I first saw it as a teenager, but now I view it as two movies in one: just as The Exorcist folded the stories of a priest wrestling with his faith and a single mother juggling parenthood and her career into its paranormal narrative, Ghost Story’s ruminations on weakness (moral and physical), the weight of age-old secrets, the realization at the end of a long life that you don’t know your spouse at all, and the ways in which parental sins are revisited on children are all implanted—well, in a ghost story. One that’s actually less compelling than any of its side concerns.

When Astaire’s character promises that if he survives this last reckoning, he’ll take his wife (Patricia Neal, another legend) to France and tell her the story of his life—and slings the tail of his scarf over his shoulder—the audience is palpably stirred, especially those members who’ve seen him don a scarf and beat a stylish retreat so many times before. Where the other films (save for Flesh Feast) pleasingly skim the surface of their stars’ images and expertise, Ghost Story delves deeper, asking more from its four leads, whose portrayals meld their enduring charm, time-honed technique, and visible infirmity into an effect as elegiac as the New England breeze swirling mournfully outside one’s bedroom window. 🩸

is the copy editor for Field of Vision’s online journal Field Notes and for Film Comment magazine, as well as a frequent contributor to Film Comment, Metrograph’s Journal, and other publications. He wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.

Sometimes all it takes is one sentence to demolish everything you thought you knew about a person. In the case of James Stewart...

BY STEVEN MEARS | February 7, 2024

After he’d fundamentally abandoned Hollywood moviemaking and cast his lot with the nascent...

BY STEVEN MEARS | August 20, 2024

There’s no crueler fate for an inventive, well-crafted film than being remembered solely for its twist ending, especially with said twist divulged through a line reading that oxidized into self-parody as soon as it entered the atmosphere.

BY STEVEN MEARS | March 1, 2022

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021