Befitting a story of blue-collar desperation, Session 9 is extremely economical in its telling. From the moment the film starts, the personalities of its doomed ensemble feel lived-in and familiar, as do the literal, figurative, and supernatural dangers that permeate the abandoned mental hospital they’re working in. Their boss Gordon (Peter Mullan), a new father and small-business owner, agrees to do a job that would normally take three weeks in one in order to avoid total financial ruin. Beset by the fear of personal and professional failure—and by the physical and psychic remnants of what went on in this snake pit—Gordon alternates between a waking slumber and pure rage. As the week goes on, in purely gothic horror terms, the hospital starts winning—though that’s just one way to see it. (In my view, society wins, albeit with the help of a demonic presence.)

We live in a time when everyone is encouraged to be as productive as possible, to fuse their identity with their job or jobs, to work all the time, and to push through burnout. Session 9—and also, I would argue, The Machinist [2004]—shows what happens when you do that, and how that approach leads to these totally hellish things. Not that everything has to be “relevant” in order to be worthy of attention, but its resonance now really struck me as I rewatched it.

It’s enjoyable to hear that it translates to the here and now in some fashion. The thing that I like to explore in my films is the mind, the internal, and what can go wrong when one is overwhelmed with guilt or with mental illness or what have you. Those are timeless issues, right? If anything, we’ve all been dealing with our own issues of mental illness over the past year and a half—trying to deal with feelings of paranoia, the feeling that the world around us is falling apart, and that’s all kind of coming to a head. Again, there’s nothing new about that. Someone like Gordon [Peter Mullan], who’s a fairly recent immigrant to our country, is trying to make good. He’s got a wife and a new kid, and he’s a struggling entrepreneur, so the financial and emotional stressors of all his life are impinging on him. That’s kind of timeless.

When we cast Peter, the character evolved a little. He couldn’t do an American accent, so we just said, “Oh, we’ll make him a guy from Scotland or Ireland who’s come over here, like a lot of people in Boston have.” So the tenor shifted. It wasn’t a big theme, but there were a few moments when we pinged the immigrant experience and the idea that, if you don’t succeed and don’t go from rags to riches, it’s a blemish on your ability to assimilate. That was another little stressor that’s supposed to be hitting this character. At the very end, there’s this big shot of Peter walking down through the kitchen—serving that fucking spell, he’s killed everyone, does he even know he’s done this?—and he walks past this big American flag that’s printed on a piece of broken glass. That was my own little Easter egg—the American Dream has shattered for him.

The story itself was loosely inspired—if that’s the word—by an executive at an insurance company in Boston who, a couple years before we made the movie, came home one night and something just snapped in him—

I read that his wife had burnt the ziti.

Yeah. Something innocuous and inane was the tipping point. He killed his wife and child in this really horrific way. He had no criminal record, and he wasn’t a particularly violent person, but that one thing, snap. And he continued to go to work for the next few days as if nothing had happened, while his wife’s body was in the house. So presumably he walked by it every day and made himself something to eat. The idea that you could somehow bury the horror of what you’ve done so that you can get on with things is kind of scary to me. That’s what was going on in the movie. Even in The Machinist, too, a crime is committed, he’s repressed it, and it catches up with him. So yeah, that’s a theme, I guess. Session 9 was maybe the first iteration of that. It was the first sort of darker movie I’d made.

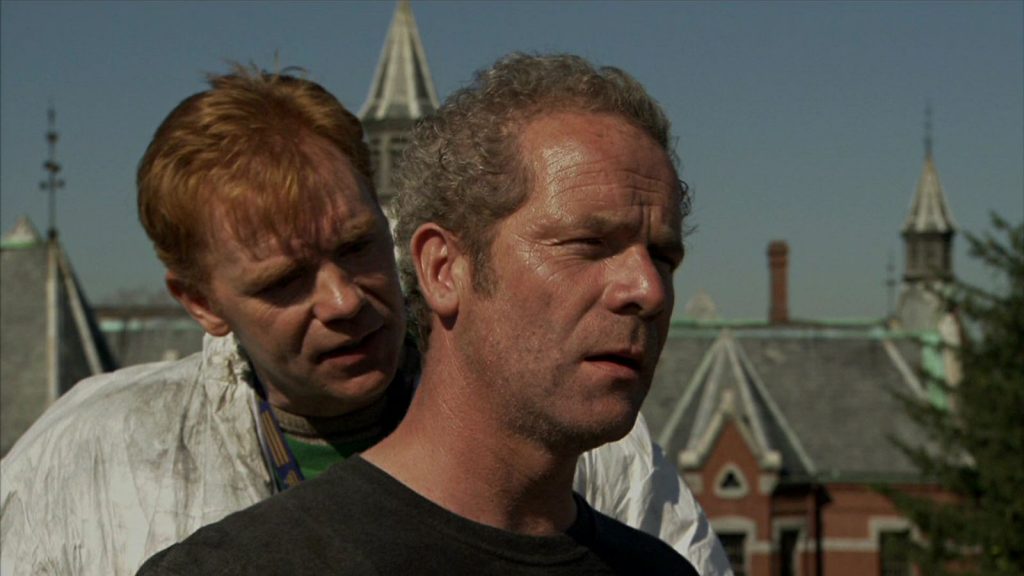

Speaking of two sides of oneself, I wanted to ask about the ensemble. As you’ve said, Gordon’s the man who’s losing the American dream. Then you’ve got Phil [David Caruso], who’s his boss’s best buddy, except for when he’s undermining him or smoking weed on the job. You have Hank [Josh Lucas], who’s a total shithead but gets the job done. You’ve got Mike [Stephen Gevedon, also the film’s co-writer], who’s the smart, rich kid, though he doesn’t act like he’s above anyone else. And then there’s Jeff [Brendan Sexton III], a total idiot who just gets sucked into this. It’s this really interesting cross section of masculinity, and they’re in this environment that’s literally toxic. I mean, obviously because of COVID, I was hyper-aware of when they’re wearing masks and when they’re not. How did you and Steven arrive at this mix of personalities?

It started with Gordon and his predicament, and then trying to create some levels around that. Each of them have their own little agendas. For instance, Hank is there because he just wants to make a little money and get the fuck out. He’s sort of skeptical about the whole thing, but he’s looking for an easy buck. And then he finds that money, that weird treasure, in the building.

Oh god, that part was the scariest shit to me. The cursed slot machine.

But that was also true. We found weird stuff in the walls of that place. They were all decrepit and falling apart. I remember someone found a book or something inside the walls—like, how the fuck did that get there?

The dynamic between Phil and Gordon is sort of a way to fuel the paranoia within the team a little bit. I’ve worked in situations like that with other dudes and, you know, every group has the quiet guy, the funny guy, and the guy who’s all about getting the job done. It was trying to color each character so it felt organic and real. At the time there were so many movies like Scream and I Know What You Did Last Summer, which were these sort of glib, more tongue-in-cheek, drive-in-movie-type horror. We wanted to do something where the horror really evolved out of character as much as it did out of the situation. Session 9 is scary because we all can identify characters like that, they could be good friends or working behind our backs, conspiring against us. On the one hand they’re a team, and on the other, they’re all doing their own thing, so you see how the team begins to sort of snap apart. Whether that’s a function of the building or something in it, or if it’s just them, is the mystery of the movie. I don’t like to spell things out. It makes for a more interesting conversation after the movie.

You mentioned that you’ve worked in similar environments with similar guys. Do you have a background in construction or deconstruction?

My dad was a home builder, so construction not destruction. My summer job was working with his men to build houses. I mean, I was usually the guy sweeping dust off the floor and picking up the nails and shit. Those semi-blue collar, working-class jobs were the kind of jobs I had growing up, and I identified more with those kinds of guys. I grew up in Connecticut, but in Boston it’s kind of like that. There’s a little machismo in those more suburban worlds. The bluster and humor that guys have with each other, we wanted to try and capture a little of that vibe, too. We didn’t want to make a movie about a bunch of teenagers who break into a mental hospital and all get offed. We wanted to make a movie with real adults.

It accurately reflects a world that is rarely depicted in film or TV anymore. Semi-blue-collar, working-class people who are just trying to get by working their asses off, getting nowhere, at the whims of their next paycheck. They don’t have that much agency. There’s nothing new about that, but so much of the horror in Session 9 grows out of that tension.

Yeah, the banality of horror. I always find scary situations that evolve out of normal things to be scarier than extreme things. It’s just like guys renovating the inside of the building and not digging into the depths of the earth or something, they’re not on a space station being attacked by aliens. They’re just like ripping down walls and cleaning asbestos, which is weird. I thought that whole aspect of it was cool. Visually, you’ve got the strange images of the guys in the white suits, which looks alien in a way, very otherworldly. The metaphor, in essence, is that everything around you could kill you if you’re not careful, and you must take precautions. As you said, there’s a toxicity in the air, both literally and figuratively. And that wouldn’t be there if they were just painters or something.

I love the otherworldliness of that shot at the end where Gordon has sort of woken up and the bodies are all laid out, but he’s in that perfect, clean, bright area where everything’s wrapped up in white plastic. It’s a very smart way to end.

The clean room in the midst of this core darkness, yeah. I really wanted to play with that idea too, of shooting the horror in the broad daylight. The more Hollywood version of that ending would have been night and darkness. The contrast between horror in the daylight is, to me, always scary—you can’t hide anything. It’s right there. That was another kind of way to buck the tropes of the horror genre a little.

I was reading an interview with Steven where he mentioned that the two of you were inspired in part by Burnt Offerings, the great Karen Black/Oliver Reed gothic horror film that mostly takes place in broad daylight. Were there other movies that you guys were thinking of while you were writing or shooting the project?

Obviously, there’s a little bit of Kubrick in there with the sense of the scope, this big place on a hill and sense of madness overtaking the characters. There’s a little bit of Polanski’s Repulsion. There’s a little bit of a play on the end of Don’t Look Now, the Nicolas Roeg film. Donald Sutherland isn’t aware of his own clairvoyant gift and it comes back to kind of haunt him in the end, where he’s dying and he’s realizes, “Oh my god, I had this gift and I knew it all along.” In Session 9, Gordon is unaware of the monster that lurks inside him until the very end, at that rug-pull moment. In general, I like movies that are more psychological horror than straight-out monster horror. I like those too, they’re fun, but I’m more interested in getting into the monster inside.

How did you come to cast Peter Mullan as Gordon?

He did this movie with Ken Loach called My Name Is Joe [1999], which is a social-realist depiction of a blue-collar, working-class guy who’s an alcoholic and struggling. It’s so moving and sad. When we were casting the movie, they wanted a bigger name for Gordon, but we didn’t have a big budget anyway, so it wasn’t like we were gonna get anyone they were really interested in. So it came down to who else could play that role, and I mentioned Peter because I’d seen that movie, and he’s so good, man. He plays that pathos of the struggling guy so well, and you connect with him. But he can be scary, too.

All of the guys were great. Caruso came in late in the game. We’d already started prepping the movie and the people who made the movie wanted to put a name in for the role of Phil, and we went through a whole list. We went out to different people who were going to do it but then couldn’t for various reasons, and then they wanted to put a musician in the role, like Kid Rock or someone.

Oh god.

Just because they thought it would be cool. Carson Daly was an executive producer on the movie. I’m not sure why—I think he was friends with the guy who ran USA Films. Point being, at the last minute, we didn’t have the role cast and David Caruso’s name came up and he was willing to do it. This was before his big turn in CSI: Miami, and he was a hungrier for work. He was a totally-into-it guy, sweet and excited, a team player. We shot the movie in 21 days. We didn’t have the time to waste because of budgets and in fact the city of Danvers gave us permission to shoot there reluctantly because it was dangerous. There were only certain places we could go.

I’m sure you know, but they’ve turned Danvers Hospital into condos.

I’ve been there. Like the name of the neighborhood, it’s called “The Avalon” or “The Avalon Suites.” It’s so bizarre. A few years back, I drove up there because I was curious, and it’s all been taken down. They’ve saved the infrastructure from some of the older, more classic buildings and made them into the main building of what the condos spill out from. But in all of the literature where they’re trying to sell you a condo, they don’t mention that it was an asylum. There’s a quick reference—it was a hospital—they don’t want to scare away potential buyers. I pretended to be a potential buyer while I was there, and the guy was pitching me the “great, beautiful grounds,” but he didn’t mention anything about the hospital. That would be the sequel to the movie: a condominium built on an old asylum.

You and Stephen were trying to get a prequel, Session 1, off the ground.

We were. We started writing it and putting it together just last year. It was going to be the Mary Hobbes story, the woman we’re introduced to in the session tapes. It would’ve been set in the early ’60s, when Mary was 12- or 14-year-old girl and followed her as she loses it and slaughters her whole family. And then it would become about her as an adult with multiple personality disorder. It was all set in the world of late-’50s hangover Americana, dad sitting down after work with his bourbon and reading The Wall Street Journal. Unfortunately the company that owns the rights to Session 9 didn’t want to relinquish the sequel rights. And we’re still kind of fighting it, we think it’s ridiculous, like what do they care? In order to do it, we’d need to have them sign off on that, and they haven’t. It would be fun to do it. 🩸

is the author of David Cronenberg: Clinical Trials. She is the former digital producer at Film Comment and the host of its podcast, as well as former VP of Digital at Harper’s Magazine.

Bryan Bertino scares the daylights out of me. It’s axiomatic that horror movies are the stuff of nightmares, but I can’t think of another director whose movies so thoroughly approximate...

BY PAUL FELTEN | December 2, 2025

Lucile Hadžihalilović has an exquisite talent for exploring the unique, manic hells that flow forth from helicopter parenting. That particular euphemism, however, is perhaps a bit too polite...

BY VIOLET LUCCA | August 12, 2022

Jennifer Reeder is a proudly Chicago-based, truly independent filmmaker with over 25 years of experience in the business.

BY MARGARET BARTON-FUMO | May 10, 2022

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021