If you want to have some fun with your fellow horror film aficionados, ask them what they’d rate as the single most effective scene for mood and atmosphere in any of the Universal monster movies. It’ll take about a second for someone to cite the creation scene in Frankenstein. A vote is bound to be cast for Lon Chaney Jr.’s first lupine dissolve sequence in The Wolf Man. The Gill-man swimming ominously beneath Julia Adams in Creature from the Black Lagoon is a contender, as well as Renfield cackling up at us from the ship’s hold in Dracula.

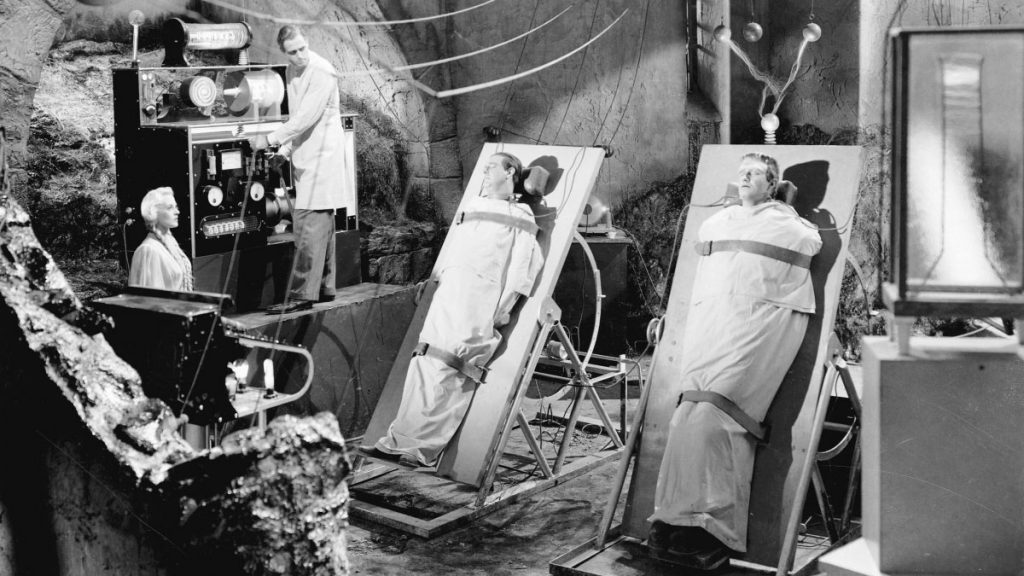

But a scene tucked away inside a crypt at the start of the film embodying the full-ripened Universal monster experience may be the worthiest choice of all. Hitchcock spoke of pure cinema; the opening of 1943’s Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man is pure horror cinema, the perfect distillation of what we’ve come for and what gets us going.

It’s night, there’s a full moon, and two grave robbers are seeking treasures in the tomb that holds the remains of that poor, cursed sad sack, Larry Talbot. Getting inside this tomb—via a window at the top of one of these unrelenting stone walls—is its own struggle, which means leaving in a hurry would make for a bigger problem. The thieves pop the lid on the coffin and discover wolfsbane atop the body contained therein. Lest we don’t know what this means, writer Curt Siodmak has one of the men recite the now-familiar folk poem from the first Wolf Man picture, which, conveniently, Siodmak also wrote. Cue the moonlight that streams through the windows of the crypt. We want to shout, “Get out of there!” but by now it’s too late anyway: a throat is about to be ripped open.

These were grave robbers, so not the most honorable fellows, but they managed to be likable, which doesn’t preclude one of them from meeting a bad end while his mate leaves him to it. Talk about a tone-setter. The scene—which plays for a full five minutes, very unusual with these sorts of things—causes us to feel as if we’re trapped, too. How are we going to watch the movie if we can’t survive its opening? Problems, problems, problems. But thankfully, it doesn’t work quite like that—which doesn’t lessen the effect.

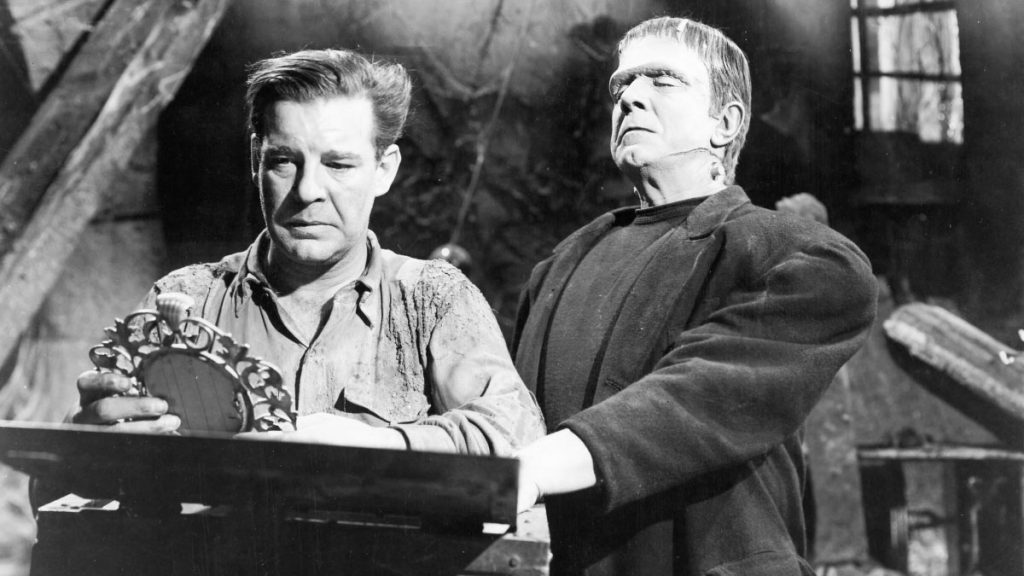

Learning of the film’s gambit—which the poster art makes plain—the horror fan (especially a kid) was/is bound to think, “No way!” As in, were these two monsters really going to share screen time? Would they fight? Of course! Who would win? Was this really happening? You want to make your audience think, “No way!” but in a manner that has them on your side—as in, “Yeah! We’re really doing this!”—rather than doubting your wisdom or motives in putting this thing up on the screen.

Chaney, naturally, is the Wolf Man, and Bela Lugosi the Monster, by which is really meant, Frankenstein. A totemic shift in the popular culture had occurred. If you ever sat in an English class and the instructor asked why it was that people called the Monster in Mary Shelley’s novel by Frankenstein’s name—because you know how English teachers like that deep stuff—this would have been your chance to say, “It’s mostly on account of this old horror film called Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man,” which would have been amusing—because what’s a teacher going to say to that?—and essentially true.

This is a good-faith picture, which is worth noting because it wasn’t long before Universal started roping all their ghouls together, given that it was easy to do so, and more monsters meant more kids in attendance in Universal’s fiduciary estimation. Those weren’t integrated affairs that told stories, but rather monster conventions that happened to be movies.

Roy William Neill directs, and while he may not have been an auteur, he had his own style. You know when it’s a Neill picture. He’s a classic stylistic craftsman of horror, along with Terence Fisher and Jack Arnold. Deftness and professionalism are in ample evidence, but there’s also an individualistic touch, a cinematic imprimatur. The lighting borders on noir-like, and some of the compositions look like they were just made to be gorgeous stills in a horror film reference book you thumb through again and again.

Those who have seen Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man almost always remember it fondly. It’s a pleaser. The promised thrills—and the thrills built up in our expectations by the movie’s title alone—are delivered. You can revisit it throughout your life and always be made happy, with the movie seeming to recharge one’s love not only for the Universal monsters but the very idea of watching a horror film. 🩸

is the author of eight books, including the story collection, If You [ ]: Fabula, Fantasy, F**kery, Hope, a 33 1/3 volume on Sam Cooke’s Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, Meatheads Say the Realest Things: A Satirical (Short) Novel of the Last Bro, and a book about 1951’s Scrooge as the ultimate horror film. His work has appeared in Harper’s, The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, The Daily Beast, Cineaste, Film Comment, Sight and Sound, JazzTimes, The New Yorker, The Guardian, and many other venues. He’s completing a book called And the Skin Was Gone: Essays on Works of Horror Art. His website is colinfleminglit.com, where he maintains the Many Moments More journal, which, at 2.7 million words and counting as of autumn 2023, is the longest sustained work of literature in history.

Anyone can watch a hearse-load of scary movies at Halloween—and lots of us do—but how many of those people try and seek out the films most indebted to, or representative of, the holiday...

BY COLIN FLEMING | OCTOBER 15, 2024

The early monstrous mass of Universal bogeys put down roots in the pop-culture zeitgeist as deep as any to be found in the most ancient burial grounds. The mesmeric hold of Dracula...

BY COLIN FLEMING | October 26, 2025

A place where no actual blood was spilled—at least to my knowledge—my grandmother’s house proved strangely—even sagely—sanguinary as it pertained to an important development in my life.

BY COLIN FLEMING | June 19, 2024

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021