Horror stories know something that other stories don’t. William S. Burroughs named his book Naked Lunch after that “frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” That’s how I remember my first horror movies: as a series of bright reveals, shocks bracketed by darkness and seared into my brain. Maybe like the opening flashbulb shots in Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre—fingertips, ankle, jawbone—the corpse in advanced decay. Like secrets you aren’t ready to know.

It’s hard to nail down the moment when I fell in love with horror because I watched everything as a kid. My mom introduced me to classics from the 1930s and ’40s—anything with espionage or Alec Guinness. Alone on Saturday afternoons, I watched Creature Double Feature, with its endless B-movies from every era and studio, on Channel 48 in Philadelphia. The Universal and Hammer films were my favorites. One moment, Dracula was Bela Lugosi, a swaggering hound at a dinner party; the next he was Christopher Lee, a feral cat found hissing in the attic. There was nightmare material here and in Attack of the Mushroom People / Matango and The Incredible 2-Headed Transplant, but there was comfort too, because the thrills were expected and safety-pinned between TV commercials. And mostly, the monsters were thwarted in the end.

The real seeds of horror were planted, as they so often are, at an all-boys Catholic school. In the early ’80s, I was a naïve only child, dazed by my first run-ins with other living souls my age. Though I seldom spoke, I listened closely, because the oral tradition was alive and well on the playground. On Mondays, 10-year-olds would return like timeworn mariners from their weekends to deliver glitter-eyed accounts of movies I wasn’t allowed to see. (Rated-R movies were the forbidden fruit.) In the tales they told, there were geysers of blood, worm-ridden faces, and curse words we echoed in whispers without understanding. I still remember vivid scenes from The Shining, The Fog, and Halloween III: Season of the Witch that aren’t in those movies at all, but were improvised by tellers eager to please. I resolved to see one of these things for myself.

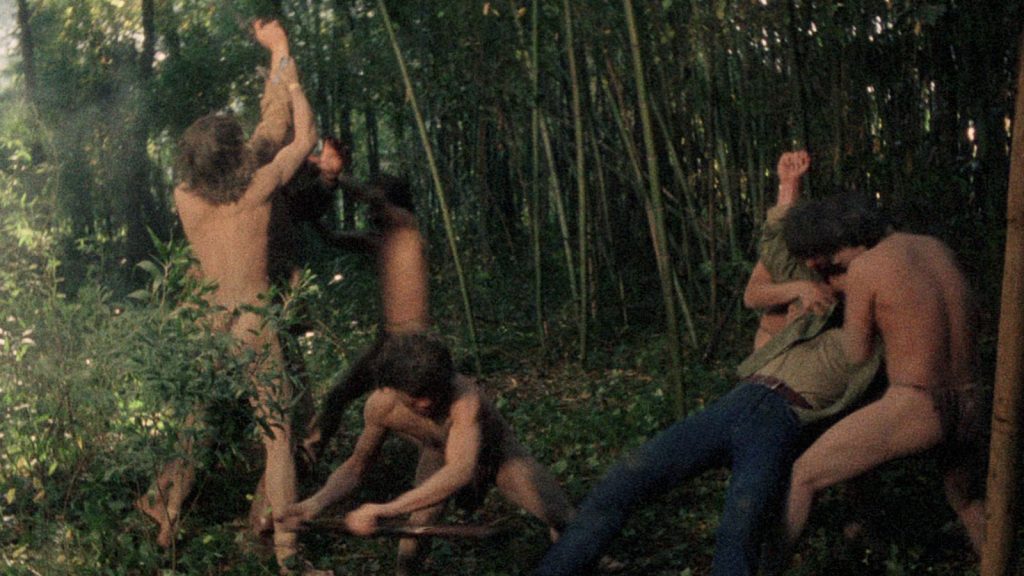

One of the storytellers was Clark, my closest thing to a friend. He had lazy parents and cable television, so our cunning brains contrived a sleepover. I think he just wanted to see my face as I took in the middle frames of Doctor Butcher, M.D. (aka Zombie Holocaust), in which island cannibals tear two men apart and eat their insides, saving for last the eyeballs. It wasn’t the first of the movies we watched, but it made an impression. I felt nauseous, so Clark reassured me by telling me that everything in the film was real. Though I know now that Dr. Butcher wasn’t a genuine medical doctor practicing on corpses, the damage was done. The veil before reality had been ripped away: I began to wonder if anything that the priests and after-school specials had told us about the world was true.

Other images branded my memory that weekend: the monster bursting out of John Hurt’s chest in Alien; the boomerang kill in The Road Warrior; the president’s severed finger in the palm of Romero, a character from my nightmares, in Escape from New York. But what captivated me most was the first thing we watched: Salem’s Lot. This was Tobe Hooper’s 1979 adaptation of Stephen King’s vampire story—a future favorite novel I wouldn’t be allowed to read for another five years. We caught it toward the end. Clark turned on HBO, and the first thing I saw was Straker, the vampire’s associate, as a door in the creepy Marsten House ripped open to reveal him. I knew James Mason from North by Northwest, one of my mom’s favorites, but he was seedier and less charismatic here. I was appalled to watch him lift a grown man by his shoulders, carry him over to a crimson wall, and impale him on a protruding array of animal horns.

The real moment for me came a few scenes later. In the basement, young Mark Petrie (Lance Kerwin) looks on as Ben Mears (David Soul), a writer and ally to the boy, drives a stake into the vampire Barlow’s heart. Over Mark’s shoulder, seen out of focus, the vampire underlings are stirring awake in the root cellar—they slither toward him with hands grasping. Gone were the vampires of faraway European castles. The real monsters were here, and they once were your friends and family. Killing the master only scattered them into hiding. Those hands and glowing eyes are what I see in shadows even now when I’m walking in the dark.

Soon after the sleepover, my friend stopped inviting me to his house. Maybe I was too serious or fearful of things—I didn’t really know how to act around other kids. But the weekend changed me and altered forever what I wanted from movies. Comfort no longer seemed possible. I felt like Mark, alone in his bedroom trying to fix his monster toys, moments before death—the real and only secret—arrives to claim his parents. I began looking for films that shocked me with things regular films didn’t provide. I wanted a kind of truth, in the darkest form available.

The rest of my childhood and adolescence passed in a steady, whirling buzz of videotape. Once VHS came to our house in 1987, my parents relaxed the rules because if I was at home watching The Lair of the White Worm—they may well have reasoned—then I wasn’t out egging houses or getting girls pregnant. So I gorged on anything with a lurid cover promising a counterpoint to theology class: Re-Animator, Hellraiser, The Wicker Man, Dawn of the Dead, Scanners, and so on. In high school, once I’d exhausted the video store’s horror shelves, I wandered into the art-house section, where I discovered Ingmar Bergman and found the same revelatory shocks in Persona (doppelgängers!), The Virgin Spring (medieval home invasion!), and Through a Glass Darkly (God’s a spider!) that I craved in horror. Learning that Wes Craven reimagined that middle one as Last House on the Left only confirmed my belief that horror has its tendrils in most stories, as sure as it has its tendrils in me.

I’m in the middle of my own life’s story if I’m lucky, well past my first shocks. I feel less like Mark, and more like Ben Mears, the writer in Salem’s Lot who wandered into a haunted house as a child and never found his way out again. He’s obsessed with an evil he can’t understand, as if death holds the answer he seeks, lurking around the next dark corner. I’m still watching the old films, and a few new ones, in search of the perfect totemic moment to expose and protect me from my own worst fears—of crowds, of contagion, of blood. And as I wait for the final secret to be revealed, horror has never felt so alive. 🩸

a writer living outside Philadelphia, is currently working on a horror project set in western Pennsylvania. He co-wrote the movie Anamorph, starring Willem Dafoe.

Item 1 on my list of demands to be met before returning to regular Mass on Sundays is the canonization of Ken Russell. In The Lair of the White Worm (1988), the whisky priest of excess directs a half-cracked...

BY TOM PHELAN | January 5, 2024

The way horror film series typically work is that the first entry is notable, for whatever reason—it’s a great movie, it’s popular, it infiltrates the news cycle/culture—and then subsequent...

BY COLIN FLEMING | October 31, 2023

One of the earliest memories I have is of my father pointing to an abandoned rowboat in Dublin’s River Tolka and quite matter-of-factly stating that “a monster lives in there.”

BY GLENN McQUAID | October 31, 2021

This pre-Code offering packs a lot of story into its typically brisk running time, with several plot threads weaving together a (not always successful) tapestry of spooky and criminal doings.

READ MORE >

BY ANN OLSSON | Month 00, 2021

In what could be the fastest-resulting rape revenge movie, a drunken lout brutally forces himself on Ida, the young woman who doesn't return his affections, during a party over Labor Day.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021

Beast is a lot of movies in one package - fractured fairy tale, belated-coming-of-age story, psychological drama, regional horror film - but above all it's a calling card for its leading lady, Jessie Buckley.

READ MORE >

BY LAURA KERN | Month 00, 2021